🎧 [PLAYBACK: SOUND ON]

Cue the music. Your reading starts here. Prince’s “319” is the vibe.

🟢 Ready to commit? Open the soundtrack in Spotify, or jump to “319” and we’re off.

DRESSING IT DOWN

Showgirls is the epitome of a film that defies rating.

It’s less a misunderstood masterpiece than a misinterpreted masterprank.

Director Paul Verhoeven’s greatest provocations (Showgirls included) have always been absurdist on their face — and when his unique brand of satire doesn’t land cleanly, his films were left to rise or fall solely on the sheer strength of their spectacle.

That’s not entirely fair.

What many initially mistook for incompetence was, more often than not, overcommitment to a bit the mainstream simply wasn’t in on.

None of it was ever meant to be subtle.

That was the whole joke.

The Satire Was Always the Point

I’m not here to join the throngs of Film Bros anointing Showgirls “The Best Bad Movie Ever Made” — a take that flattens its contradictions and entirely misses the point.

I’m here to remind you that Paul Verhoeven, one of cinema’s most brilliant and underappreciated satirical provocateurs, never made a film that wasn’t also a personal dare. Except Hollow Man.

There’s a reason the debate over whether Showgirls is “bad” rages on to this day. Verhoeven’s signature subversions don’t always survive the genres they’re skewering. And this picture is no exception.

Thankfully, the naysaying crowd has shrunken over time — like those who still won’t admit that Die Hard is, and always has been, a Christmas movie. Showgirls, incidentally, is *also* a Christmas movie. But that’s a conversation for another time.

Even if you somehow wind up hating it, if you're at all serious about cinema, it's worth understanding what kind of powder keg led to this film’s coronation at the pinnacle of camp cult status. For the past quarter century, no other legendary misfire has burned so brightly.

I long held Showgirls at ★★★½ — roughly analogous to “REVELATION” on the SINemeter scale today. But it isn’t just a revelation. While not every element secretly works (though most do), despite its flaws, it’s an absolutely essential film.

I can’t think of another studio picture this simultaneously luxe, chaotic, proudly tasteless — and, somehow, still... kinda brilliant.

It’s a brazenly unique cinematic enigma.

Welcome to Vegas, Baby

To be clear, Showgirls is a gloriously spectacular trainwreck that makes nudity tedious and sex farcical.

But it's done in such a garish, vulgar, over-the-top manner that makes it impossible to look away as the film unfolds. It may be mind-blowingly absurd in every aspect imaginable, but it's never boring.

It is also not, as the poster would have you believe, a movie about a woman with no arms and one leg, nor is it the feminist masterpiece some critics revisionistically claim it to be today.

We’re first introduced to our protagonist, Nomi Malone (“No, me alone,” get it?), as she hitchhikes to Vegas, pulls a blade on her driver, hits jackpot her first time at the slots, subsequently goes broke, gets robbed of every earthly belonging, attempts suicide by traffic on the Strip, vomits in a parking lot, assaults a basket of French fries and finds a new, lifelong best friend.

And that’s just the first seven minutes of the picture.

Subscribe free for more cult reappraisals, misunderstood masterpieces, and box office disasters too dazzling to dismiss.

Berkley Didn’t Fall — Hollywood Did

Star Elizabeth Berkley, having recently graduated from both high school and TV’s Saved by the Bell, gives some of the worst line readings in the history of cinema, certainly for a major theatrical release, enough to spawn a (surprisingly good) musical stage production imitating her performance.

Shockingly, she was only paid $100k for the lead role in a $45 million picture, while director Paul Verhoeven made $6 million (two-thirds of which was withheld when the film tanked theatrically) and screenwriter Joe Eszterhas a then-record-breaking $3.7 million — all, ironically, while making a film satirizing the entertainment industry's exploitation of women.

So, the studio got from Berkley *exactly* what they paid for. And I say, "Good for her!" It's just a shame that her career was destroyed in the process.

Yes, Verhoeven knew precisely what he was doing in crafting a sleazy remake of All About Eve while casting a sharp eye of criticism at American culture — as he did with every one of his U.S.-made films throughout the ’80s and ’90s.

But even he admits that how he went about it was simply too esoteric for most audiences at the time, particularly in the face of the studio’s mis-marketing of the picture as one of the most daringly erotic ever made. (He's described the film as purposefully “anti-erotic,” and he’s right.)

Quite tellingly, MGM opted to release Showgirls, at the last minute, under its niche United Artists banner instead — the intact ‘spelling-it-backwards’ audition joke be damned — in a last-ditch attempt to shield the parent brand from what they fully knew was coming.

Verhoeven has also since taken responsibility for Berkley’s performance, noting that much of it was the direct result of his explicit instructions to her on set — deliberately pushing her line delivery beyond anything remotely resembling a natural read.

On the writing front, Eszterhas' ceaselessly inane dialogue seems as if it were created by aliens who learned our language by pointing two microphones at Earth: one toward a juvenile detention facility and the other aimed at a porn theater. They spliced the two recordings together in random order and determined that's how people actually speak to one another on this planet.

I recall reading some time ago that Eszterhas admitted to writing Showgirls holed up in his home on Maui while on a two-week cocaine-and-booze bender and doesn't remember penning a word of it. But I can't find that reference today, so take the story with a grain of salt.

In his autobiography, Hollywood Animal, his recollections of developing the script consist solely of daily journal entries, having been on an unnamed substance plied to him by a local dealer, and his wife Naomi despising it upon first read.

However, the full-on cokefest story would’ve at least offered some explanation as to what the hell happened here.

What Happens When No One Says No

Aside from Berkley, the performances in Showgirls are all over the place.

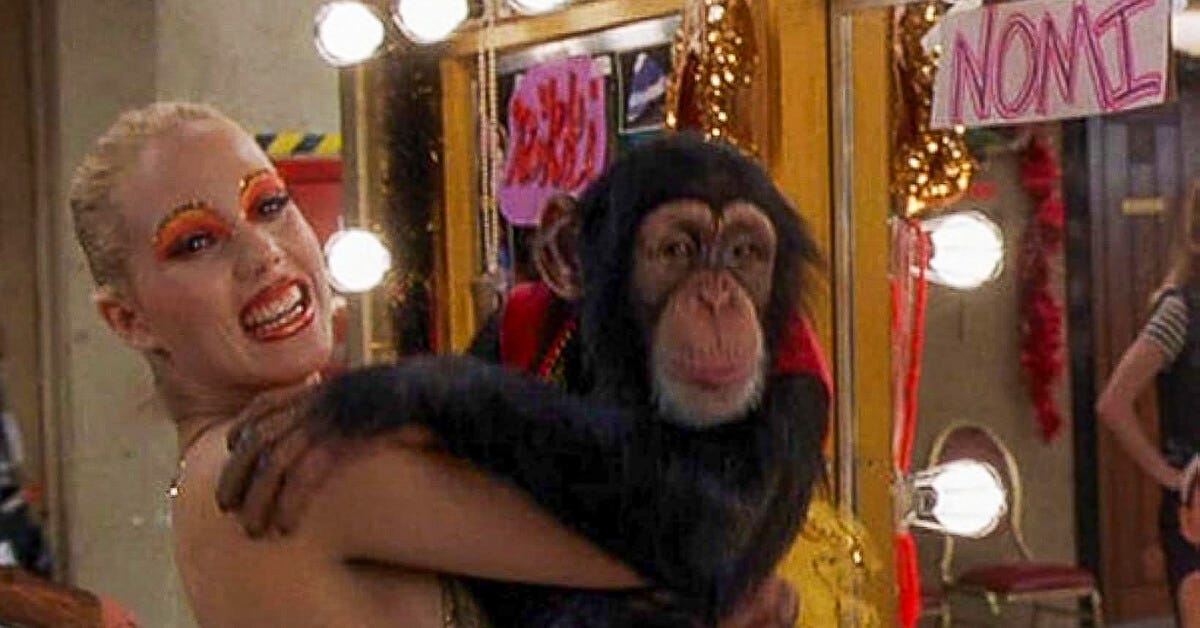

While MVPs Gina Gershon, Robert Davi, and L.A. Law's Alan Rachins (R.I.P.) seem to be having a blast leaning into the unapologetic trashiness of their characters, others like Kyle MacLachlan and Glenn Plummer rightfully just seem embarrassed.

As the main character's best friend, Gina Ravera (The Closer, Lambada) gives by far the most grounded performance in an otherwise thankless role as subject of the film's most mean-spirited and regrettable sequence.

It’s the narrative equivalent of shooting a baby seal in the head after it’s already been bludgeoned to death — so unnecessary that it nearly destroys Showgirls' candidacy as a guilty pleasure.

Most die-hard fans (myself included) understandably compartmentalize that scene out of memory. Both Verhoeven and Eszterhas have independently singled its inclusion as their biggest mistake with the picture. And that was a deep well to draw from, to be sure.

It shouldn't be lost on Verhoeven fans that the actors playing two of the picture's most memorably odious supporting characters, Ungela Brockman as verbally abusive lead understudy Annie and Greg Travis as slimeball PR agent/talent scout/pimp Phil Newkirk, were both cast in the director's follow-up film Starship Troopers two years later, only to be immediately dispatched by particularly gruesome means.

Meta commentary, perhaps? You decide.

Its Rating Broke the System

Although Verhoeven proactively self-censored his original assemblies of both the lap dance and infamous pool scene to avoid being refused a rating altogether, Showgirls never seems to make the most of its intentional NC-17.

Roger Ebert — one of the original champions behind NC-17’s 1989 creation as a legitimate adult rating (without the porn-adjacent baggage of X) — was initially excited to see the reluctant studio system finally embrace it. When Verhoeven’s project was announced, he hailed it as a chance for American filmmakers to claim the kind of freedom long afforded their international counterparts.

Until that point, NC-17 mainly had been reserved for imported arthouse fare, like Henry & June and The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover. So when Showgirls finally arrived in 1995 as a big-budget, high-profile, (relatively) wide-release film carrying that badge, Ebert was ready to celebrate the breakthrough.

Instead, he gave it two stars and called it “a perfectly good waste of an NC-17 rating.”

He wasn’t entirely wrong. We may disagree regarding the quality and impact of Showgirls (Ebert seldom vibed with most of Verhoeven’s satire.) But the director’s cut of his previous picture, Basic Instinct, is more explicit. Even by the standards of today’s TV-MA streaming series on services like MAX and Netflix, Showgirls seems a bit restrained— and certainly tamer than Verhoeven’s earlier Dutch-language work (save for Soldier of Orange). Ebert recognized the wasted potential.

To his mind, Hollywood had fumbled the opportunity he’d helped secure — the chance for serious U.S. filmmakers to finally create uncut, adult-oriented work without having their distribution prospects shredded.

Yet Showgirls remains the only big-budget, studio-financed film ever released as NC-17 — and it proved the rating’s undoing. Despite its ambition, it was ultimately a pressure test that the system failed.

The film’s flop didn’t just end careers — it effectively killed NC-17 as a viable rating before any other big studio film could test it. Saddled with near-universal critical derision, queasy audiences afraid to buy tickets, and widespread advertising restrictions, despite a pretty strong per-theater opening, the film was dead on arrival.

Even worse, three of the largest theater chains — AMC, Cinemark, and, most absurdly, United Artists Theaters (the same brand and a sibling to the studio releasing the film) — refused to screen it based on internal policies barring NC-17 titles.

But the supposed moral panic and pearl-clutching proved more theatrical than the film itself. At the video store, Showgirls found its audience immediately — and then some. Curiosity turned into cult obsession, lore was built, and what began as a cautionary tale became a camp classic with a redemption arc worthy of a Vegas comeback.

Cult Canonization Fully Earned

Showgirls’ ultimate legacy wasn’t built by critics or collectors — it first came first from LGBTQ+ audiences who never needed the memo. While mainstream culture recoiled, the gay community embraced Showgirls from the start as the deliciously messy spectacle it was always meant to be.

Nowhere was that more visible than in SINephile’s hometown of San Francisco, where drag icon Peaches Christ turned it into an annual tradition at the Castro Theater — screening the film accompanied by stage re-enactments of iconic scenes for sold-out crowds over two decades.

Showgirls wasn’t just reappraised. It was revived, worshipped, and imitated in costume (or lack thereof) until the rest of the world finally caught on. Call it redemption, or just recognition arriving fashionably late.

Appropriately, it’s now found a home on the streaming channel of our founder’s former stomping ground, Criterion, right where it belongs.

For fun, try tracking down a copy of the edited-for-TV version (supercut below), which it's hard to believe even exists, and from which Verhoeven removed his name.

After cutting almost 1/3 of the film deemed completely unsalvageable, they managed to retain 84 minutes by dubbing over practically every other line of remaining dialogue and digitally painting cartoon tops on all of the dancers à la Jessica Rabbit.

As a final affront fitting of the film, the studio even refused to pay Berkley a requested $5k fee to perform the massive amount of voiceover work required to patch nearly all of her dialogue for the TV edit. So they substituted an actress who sounds like she was inhaling from a helium balloon between each turn at the mic.

And, yes, that somehow makes Showgirls even more fun and uniquely precious than it already was.

OK, LET'S LINE 'EM UP

+ 2 points for showing what happens when you attempt to murder a bottle of Heinz 57

+ 2 points for introducing Nomi's new backstage station at the Stardust by pulling down the name tag "Drew.” (Drew Barrymore was first offered the role but wisely turned it down.)

+ 3 points for the original inspiration for a modern-day reboot of All About Eve being a late-80s lunchtime pitch to Eszterhas from none other than... Jane Fonda, envisioning herself in the Bette Davis/Gina Gershon role. Thanks, Jane!

+ 5 points for choreographing the main sex scene to look more like an in-pool epileptic seizure by an actress with no understanding of where human genitals are located

+ 10 points for inadvertently functioning as a sequel to Lambada

Its journey from cinematic disaster to canonized camp classic is a masterclass in how time and irony can rescue even the most broadly derided studio flop.

If Berkley was the sacrificial lamb, then the audience was the cult. And somehow, 30 years on, Showgirls has more believers singing its praises than ever before.

A cult essential. Sharp, singular, and simply irreplaceable.

SINemeter Judgment: CANONIZED

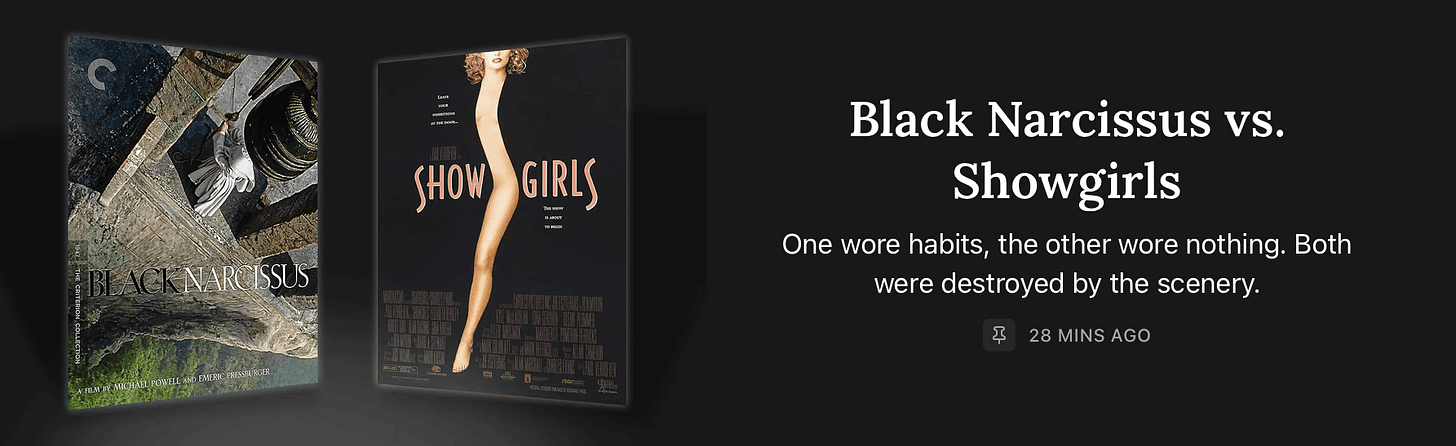

DOUBLE FEATURE DETOUR

Think Showgirls is outrageous now? Try pairing it with Powell & Pressburger’s 1947 Technicolor classic, Black Narcissus, about nuns in the Himalayas. Find out why they’re twisted siblings in the full Split Screen showdown, if you dare.

📊 [PLAYBACK: RECEPTION]

Production Budget: $45M in 1995 (~$90M now)

U.S. Theatrical Release: 1,388 theaters (wide minus AMC, Cinemark, UA)

Key Competition: Se7en, To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything Julie Newmar, ClockersOpening Weekend: $8.1M (~$16.4M today)

Opening Rank: #2 (behind Se7en)

Worldwide Box Office: $37.8M ($76M today)

Cinema DEFCON Threat Assessment: DEFCON 4

Theatrical-to-VHS Window: 3.5 months

Verdict

Opened strong, but quick drop off, earning less than half its production budget in its domestic run — thanks in part to the stigma of its NC-17 rating and limited theatrical reach.

But on home video, it became a cult sensation, grossing over $100M in VHS rentals and becoming one of MGM’s top 20 bestsellers ever.

Because so many waited for the video drop, Showgirls gets its slight ding and lands at DEFCON 4.

“People were too shy to see it in a theater. But not too shy to rent it.” — Paul Verhoeven

🎬 [PLAYBACK: TRAILER]

The NFTG original red-band theatrical trailer — because even the MPAA said, “Good luck finding two minutes of safe footage.”

Verhoeven and Gershon reminisced in a 2017 Film Society of Lincoln Center retrospective that when they first saw this trailer (and the accompanying poster art), they just sighed in exasperation because the studio misread the entire point of the film and was marketing it instead as an example of precisely the type of Hollywood output that it was crafted to mock.

THE 7 DEADLY SINS OF SHOWGIRLS

(VISUAL EDITION)

What starts with assault by French fry and ends with a shattered femur?

Verhoeven’s seven-act Machiavellian tragedy disguised as high-gloss sleaze, that’s what.

Here are the most memorable moments, among countless.

Postscript:

If you're intrigued by Showgirls, consider exploring the film that first nearly destroyed Verhoeven’s career before he even arrived in the U.S.: the tonally akin Spetters from 1980.

It marked his first pass at many of the same provocative elements — pre-sex menstrual checks, gratuitous gang rape, and yes, humans consuming dog food — all presented more graphically than even NC-17 would allow, and with far less irony. Both Spetters and Showgirls also include harrowing suicide attempts via traffic; in Spetters, it’s tragically successful (and the actor involved would sadly later succumb to the same fate in real life), adding an alienatingly grim final note to an already volatile narrative.

Pair that with Katie Tippel, Verhoeven’s earliest satire on the exploitation of women — the only film he’s ever expressed interest in remaking — and you start to trace the thematic throughline that leads straight to Showgirls. Together, they form the blueprint for this bastard American stepchild that would, for better or worse, become synonymous with his name.

Our vote: better.

Fittingly, Spetters and Showgirls were blank-check projects Verhoeven was handed immediately after career-defining hits — war epic Soldier of Orange made him a national hero in Holland, Basic Instinct a Hollywood kingmaker.

In each case, he overplayed his hand so spectacularly that he was forced to reinvent himself in the aftermath.

But really — isn’t that exactly what makes his work so singularly great?

Share this review with your friends who own the special edition box set. And whether it sizzled or shorted out, tap like or drop your favorite line reading in the comments.