Sex, power, and deception—few genres burned hotter or crashed as hard.

The erotic thriller evolved from film noir, exploded into Hollywood excess in the ‘80s and ‘90s, and collapsed under its own weight before finding new life through international and subversive reinterpretations.

While its formal identity didn’t solidify until the Reagan era, a sort of cinematic backhand to the social conservatism of the day, the genre’s impulses go back further—through Psycho’s voyeurism, Blow-Up’s obsession, and a long tradition of noir dames who left lipstick and bodies in their wake.

These 10 films trace the rise, peak, and fall of the genre—from the femme fatale's origins to its most scandalous, stylish, and controversial heights—and where its glowing embers still smolder today.

And no, Barbara Stanwyck doesn't get naked in 1944’s Double Indemnity, you pervs... but you can't truly understand this genre without knowing where it all began.

Prelude to a Genre

Double Indemnity (1944)

The femme fatale as sexual predator is born.

Billy Wilder’s noir classic lit the match with Barbara Stanwyck’s manipulative femme fatale and the seduction-as-doom blueprint that would reverberate through decades of sweat-dripped cinema.

The Foundations of Obsession

Before the erotic thriller became a bona fide genre in its own right, it was a set of impulses—lust, suspicion, control—bubbling beneath the surface of noir and psychological dramas.

These films trace the genre’s formative stages, when female desire began to shift from cautionary tale to calculated power. Here, we see the femme fatale evolve from punishment to provocation, setting the stage for the sexual high-stakes chess matches to come.

Klute (1971)

Bridging detective noir with psychological eroticism. Jane Fonda’s call girl is independent, intelligent, and elusive—a psychological bridge between noir’s guilt and the genre’s pent-up desire to punish, control, and unravel, with Hays Code censorship safely in the rearview mirror.

Body Heat (1981)

The modern erotic thriller fully emerges from the shadows. Kathleen Turner’s femme fatale is pure danger, and this steamy, noir-inspired film set the mold for the genre’s golden era.

The 4th Man (1983)

Europe’s take on the newly emergent trend. An intensely sexual Dutch thriller introducing surreal ambiguity and bisexual stakes that Verhoeven would later repurpose and spin into Basic Instinct’s high-gloss blockbuster.

The Golden Age of Erotic Paranoia

By the late '80s, the erotic thriller had become a studio goldmine—and a cultural lightning rod.

The success of Fatal Attraction and Basic Instinct triggered an endless wave of imitators, from slick-but-empty mysteries like Sliver and Color of Night to gender-reversed riffs like Single White Female.

The erotic thriller became so ingrained in the cultural mileu of the time that even comedian Carl Reiner got in on the action with the spoof Fatal Instinct.

But beneath all the hype and hysteria, a few standouts truly earned their sweat.

Fatal Attraction (1987)

The erotic thriller goes mainstream. The film’s blend of psychosexual obsession, marital infidelity, and gender politics turned it into a box-office phenomenon, establishing the genre as a Hollywood staple.

Basic Instinct (1992)

The apex of the genre’s success and excess. Sharon Stone’s Catherine Tramell became the definitive femme fatale of modern cinema, weaponizing sex as both power and misdirection. Stanwyck crossed her legs so Stone could uncross them.

The Last Seduction (1994)

A femme fatale who plays by no one’s rules. The genre’s first major entry to grant its cold, manipulative femme fatale full unapologetic victory, breaking the moral contract audiences had come to expect for decades.

Jade (1995)

The straw that broke the genre’s back. Intended as the next Basic Instinct, this overstuffed, underbaked thriller from Joe Eszterhas and William Friedkin leaned hard into scandal and spectacle—but only revealed how quickly the formula was curdling. Jade didn’t kill the erotic thriller (careers is a different story), but it did make audiences stop taking it seriously. Director’s Cut, with its original ending intact, is the only way to watch this.

Twilight & Transgression

As the genre approached its end, it got campier, weirder, and more self-aware.

No longer a box-office staple, the erotic thriller mutated into something stranger—less about titillation, more about psychological unraveling, power flips, and internalized danger.

Wild Things (1998)

The erotic thriller as gleeful, tongue-in-cheek, self-aware trash. It pushed the genre’s sex and plot twists to absurdist new heights, reveling in its own excess and emerging as a campy sendoff.

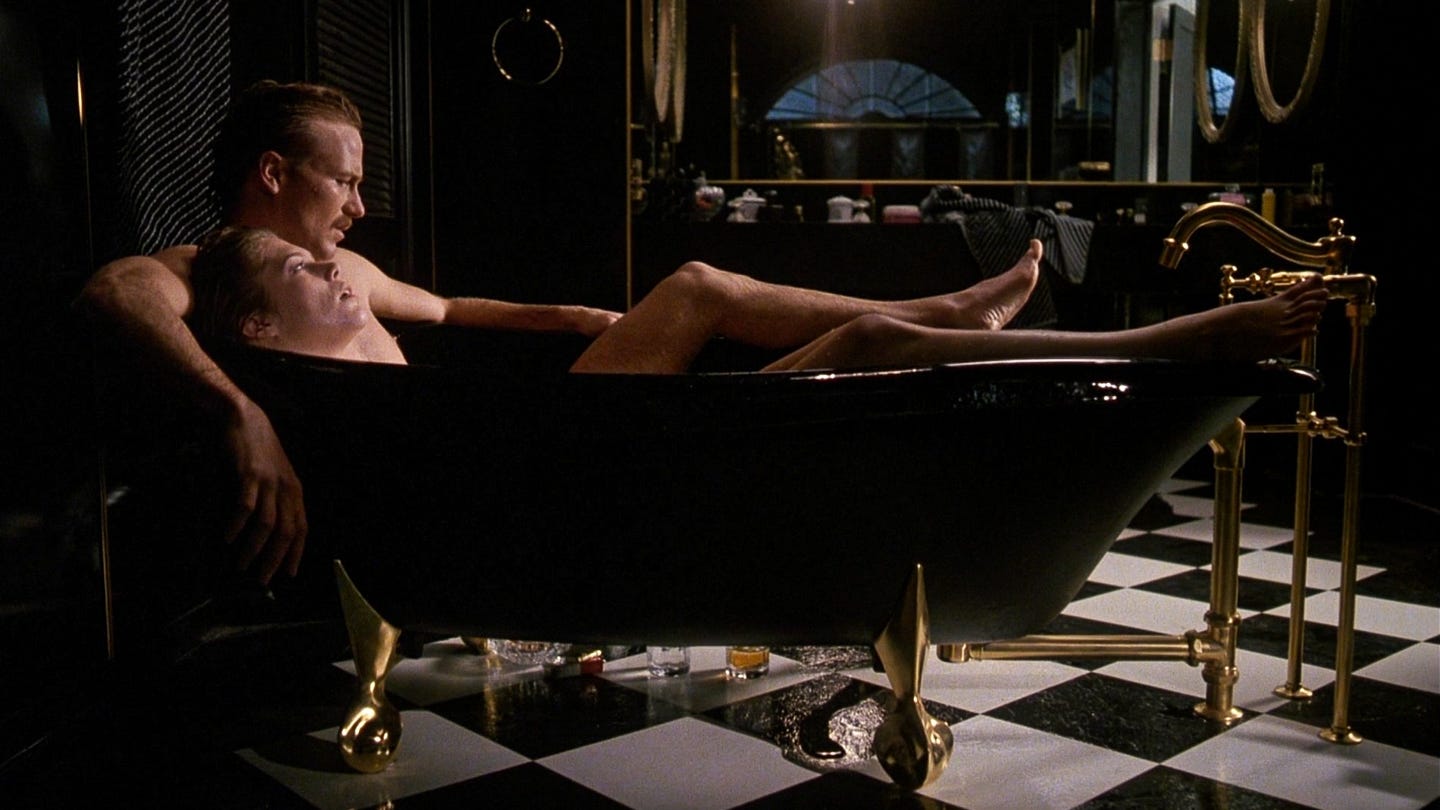

Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

One of the last major Hollywood erotic thrillers before the genre faded. It’s a perfect bridge between the ‘90s and the modern era, with Kubrick’s dreamlike eroticism and themes of infidelity, paranoia, and sexual danger.

In the Cut (2003)

The erotic thriller through a female gaze. Meg Ryan plays against type in this atmospheric, deeply psychological take on desire and danger. Jane Campion infuses the genre with a raw, female-centered perspective on eroticism, vulnerability, and violence.

The Contemporary Aftershock

The Handmaiden (2016)

The erotic thriller redefined internationally.

This lush, subversive take on the genre incorporates layered deception, lesbian desire, and historical intrigue. Park Chan-wook takes the genre’s DNA and rewrites it—queering the gaze, doubling the deception, and wrapping it in silk.

If Double Indemnity lit the fuse, The Handmaiden proves the fire still burns, hotter and smarter than ever, just not in the same way.

The Heat Left Behind

The erotic thriller hasn’t disappeared so much as it’s been teasingly awakened, fooled around with, and sadly collapsed in premature exhaustion. In today’s cinema, its presence is mainly spectral—glimpsed in reflections, borrowed in tone, but rarely embraced outright.

Adrian Lyne’s Deep Water (2022) was the most literal recent resurrection attempt: a pulpy reimagining of Eaux profondes, a little-seen French film based on an obscure Patricia Highsmith novel and once led by a young Isabelle Huppert. It was meant to be a triumphant comeback for the director who had once defined the genre's heyday.

But after two decades away largely due to the lingering fallout from his hugely controversial 1997 Lolita remake—Lyne resurfaced only to find a landscape where eroticism was no longer cinematic, danger no longer glamorous, and theatrical release no longer guaranteed. The film went straight to streaming, and vanished almost instantaneously. The genre’s funeral rites on autoplay.

And yet: the erotic thriller’s DNA stubbornly persists. Gone Girl reengineers Fatal Attraction into an algorithmic morality play. Stranger by the Lake distills the genre to pure carnal fatalism. Fair Play recasts seduction as corporate bloodsport.

These films don’t revive the genre—they perform autopsies on it, dressing its corpse in updated wardrobe (or lack thereof), then filming the afterglow.

Because the truth is, you can’t resurrect the erotic thriller intact. The reasons it once existed have long since been sidelined by DMs and OnlyFans, and the world it once aroused has largely swiped past it.

But the best qualities of the erotic thriller—obsession, voyeurism, danger made flesh—haven’t died. They’ve just evolved.