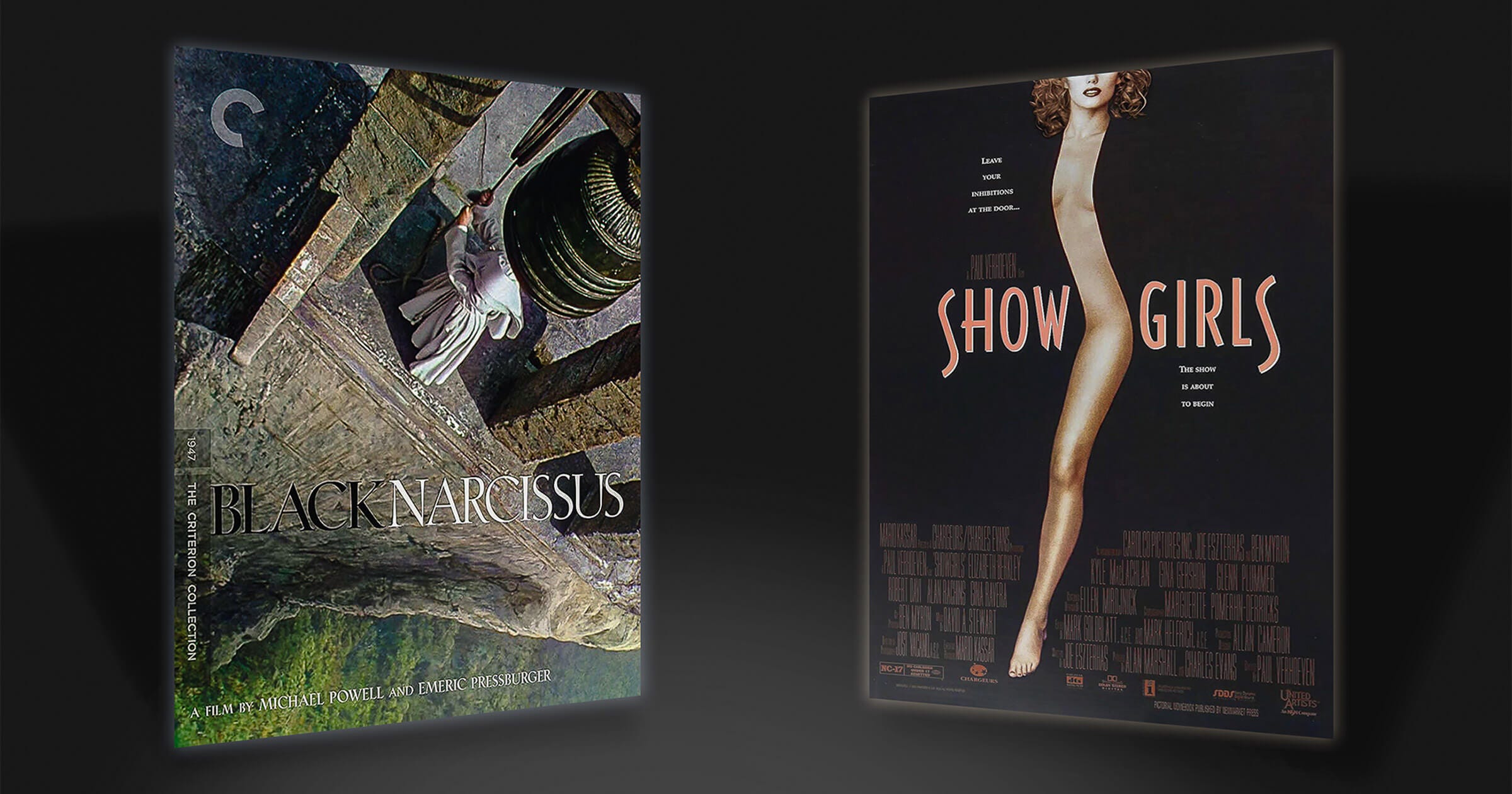

Black Narcissus vs. Showgirls

One wore habits, the other wore nothing. Both were destroyed by the scenery.

You think you know these movies. You don’t.

You’d be right to cast a skeptical eye at the mere thought of comparing a revered 1940s Technicolor masterpiece about nuns in the Himalayas to a notorious, career-killing sleaze-a-thon about Vegas strippers — the lone film that dared try to make NC-17 go mainstream.

They were made nearly a half-century apart. One was instantly canonized; the other, ruthlessly eviscerated.

And yet, Black Narcissus (1947) and Showgirls (1995) are actually the Same. Damn. Film. And we’re here to prove it to you.

Let’s get the obvious out of the way: Showgirls is often dubbed “All About Eve in a G-string” — and it almost was.

Originally pitched by Jane Fonda to ascendant screenwriter Joe Eszterhas in the late ’80s as a modern-day remake of the Bette Davis classic transported from Broadway to Hollywood (a proposed star vehicle for herself), the idea was later twisted into the unforgettable cinematic trainwreck forever stamped with his name. (Jane escaped unscathed.)

But Split Screen isn’t about the obvious comparisons. It’s about uncovering the hidden kinships between films that dare not be compared — until you realize they absolutely must be.

Posit

Both Black Narcissus and Showgirls ask the same brutal question:

What happens when a woman tries to define herself in a system that enables and profits off her rise, but is threatened by her humanity?

Virtue was Sister Clodagh’s armor. Skin was Nomi’s.

But the moment either woman let herself truly show, the Machine pushed back. Ambition wasn’t the problem. Being human was.

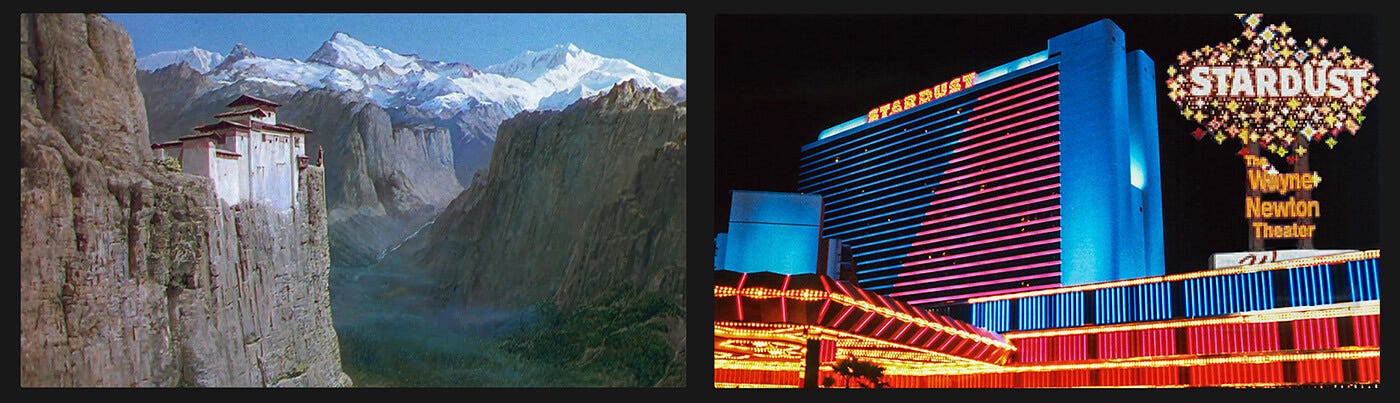

The Scenery Seduces First

From the moment they arrive, the walls are watching.

Powell and Pressburger’s harem-turned-convent clings to a Himalayan cliff — silent, ornate, precarious.

Verhoeven’s Vegas throbs with neon and chrome, every surface ready to reflect your transgressions right back at you.

One offers breathtaking views of majestic peaks. The other? Same — just garishly lit and served with bouncers and comped drinks.

Neither are passive spaces. They lure. They dare. They destroy. The Palace of Mopu and the Stardust may look nothing alike on the surface, but both are dens of iniquity built to consume the women inside them.

In each film, the setting isn’t just a backdrop. It’s a trigger. And survival depends on learning the house rules before the floor drops out from underneath you — sometimes literally.

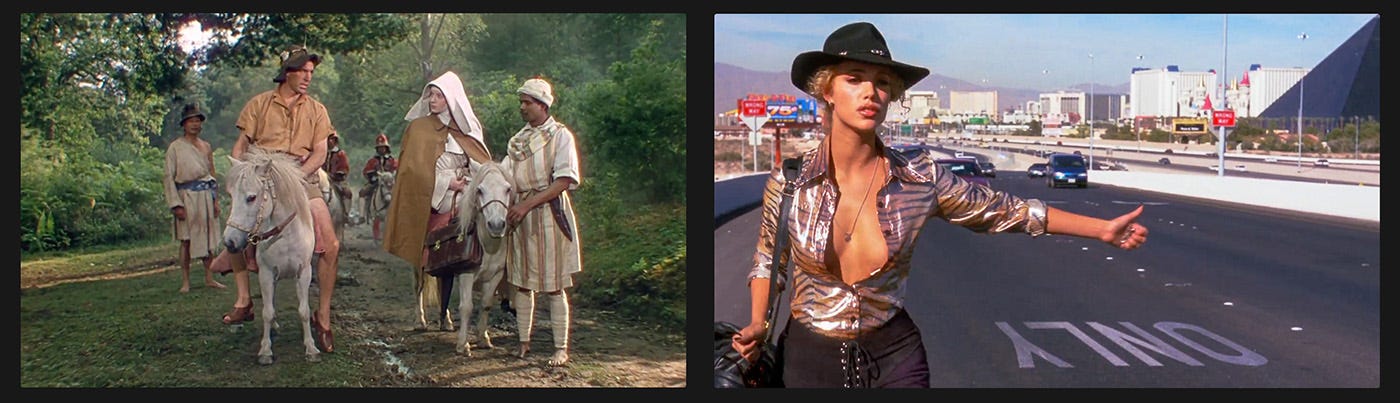

Women in Exile

Our heroines first arrive on the scene in full-on escape mode.

While Sister Clodagh evades the shame of a failed romance back in Ireland, Nomi flees her lengthy multi-state crime spree. Both land in “prestigious” institutions dressed up as opportunity. But, unbeknownst to them, reinvention carries a price.

There’s no clean slate to be found.

As much as our protagonists may have hoped otherwise, their new environments can’t erase the past, because they’re designed to capitalize off it. Alone and exposed, both women find themselves unraveling, until their planned reinvention curdles into reckoning.

Out, Out, Damned Spot!

The spots are everywhere.

It’s the first visible sign that neither place welcomes newcomers quietly and systemic rejection will inevitably leave a mark.

At the Palace of Mopu, the Sisters of Saint Faith break out in “spots” shortly after arrival — bad water, they’re told. At the Cheetah, they appear in neon, under black lights, and with the kind of invisible ink that stains reputations.

One condition is blamed on the environment. The other? Well, let’s just say they’re brought by the customers. So, no, we’re not just talking about the name of the club.

Or are we?

The Erotics of Performance

In these films, movement becomes language.

Sister Clodagh’s rigid posture breaks only when her ghostly flashbacks of a past lover say more than her vows ever could. Nomi’s violent, high-octane routines reveal not just ambition, but rage as a defense mechanism.

Sister Ruth enjoys tugging that churchbell rope a bit more than the Lord requires. Cristal leverages her star power to gleefully tug on Nomi. And both gestures directly lead to their downfall.

“I’m a dancer!” | “The Superior of all is the Servant of all.”

— Nomi Malone / Reverend Mother

What’s being sold as purity — religious or sexual — is laced with something far more volatile.

Desire exists on every axis here. It’s repressed, performed, projected. And it always comes at a cost.

The Men Are Just Props

Eight men, zero main characters.

Yes, there are males in these two movies, technically. But they’re not at all the story.

Mr. Dean and Zack Carey may flirt with centrality, but they exist solely on the periphery — accessories to female transformation, capitalizing off their attempts.

Their presence triggers tension, but it’s the women who decide the terms of engagement.

And rightfully, so.

Curious how each film stands on its own? Read the full reviews of Black Narcissus and Showgirls, complete with restored images, trivia, and righteous praise.

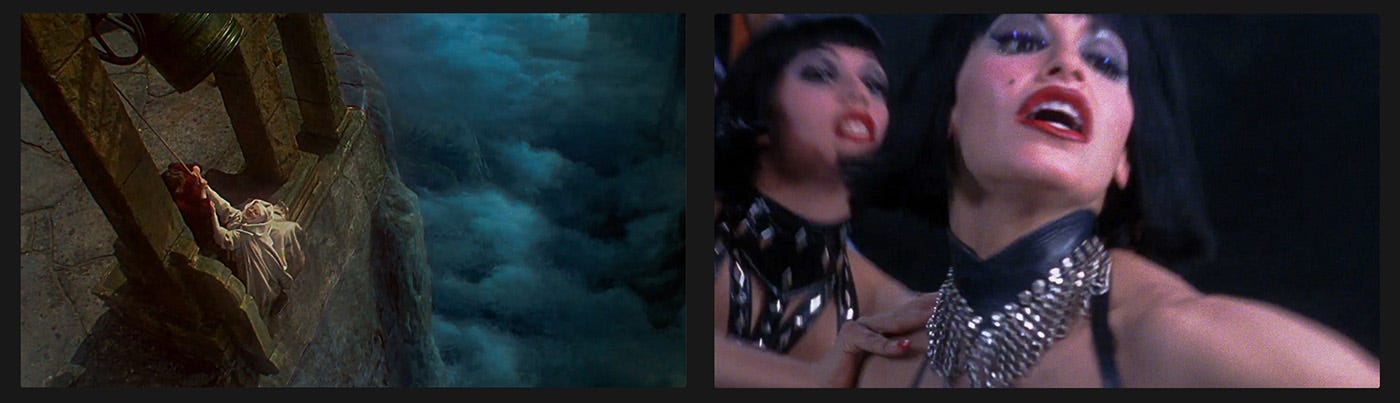

The Fall

Clodagh and Ruth, Nomi and Cristal: these are battles fought in glances and gestures, jealousy and power.

And when those power struggles meet their climax, they do so spectacularly.

One takes a dive from a thousand-foot cliff. The other woman down the backstage version of the Exorcist Stairs.

The architecture may change, but the stakes stay the same.

Revelation in Ruin

Both films end spoiled triumph and introspective clarity. And loss.

Our heroines didn’t quite win the game they set out to conquer. They willfully walk away from it.

Clodagh descends the mountain just as the rains come. Nomi hitches out of town just before the cops do. Each is altered, exposed, yet somehow still standing. And that’s the real miracle.

In environments as harsh as these, whether you were fighting for redemption or renewal, success often comes instead in the form of survival.

And for these tough ladies, that’s still a win.

Taboo for Their Day

Although emanating from very different places, both films dealt with their fair share of censorship struggles.

Black Narcissus was famously left cut for 41 years, prior to restoration in 1988. The most egregious footage apparently was flashbacks to Sister Clodagh’s life in Ireland: scenes of fishing, caroling, and a former fiancé.

The mere suggestion that a nun once had a life before Christ was considered so offensive that the film was threatened with a Hays Code ban prior to the cuts.

Ironically, the rampant phallic and yonic palace decor — enough to make a Georgia O’Keeffe painting blush — escaped scrutiny entirely, flying over everyone’s heads.

On the other hand, while Showgirls was famously permitted its NC-17 rating from the get-go, with Verhoeven wielding final cut privileges based on his blockbuster success with Basic Instinct, the MPAA didn’t offer the same blank check the studio gave him.

In order to abide by NC-17 standards and not be refused rating altogether, Verhoeven ultimately delivered softened versions of both the pool and lapdance sequences than those he’d originally assembled.

At least NC-17 meant the film could still achieve a relatively wide theatrical release, with Verhoven noting, “We pushed the boundaries as far as we could, but we were still mindful of the MPAA. We didn’t want an unrated movie — nobody would show it.”

Ironically, even after the edits, both films were banned in Ireland. Black Narcissus for being an affront to religion. They didn’t give a reason on Showgirls, as if they needed to. But Verhoeven’s film shockingly didn’t pass certification in the country for over two decades, finally officially landing on home video for the first time there in 2017.

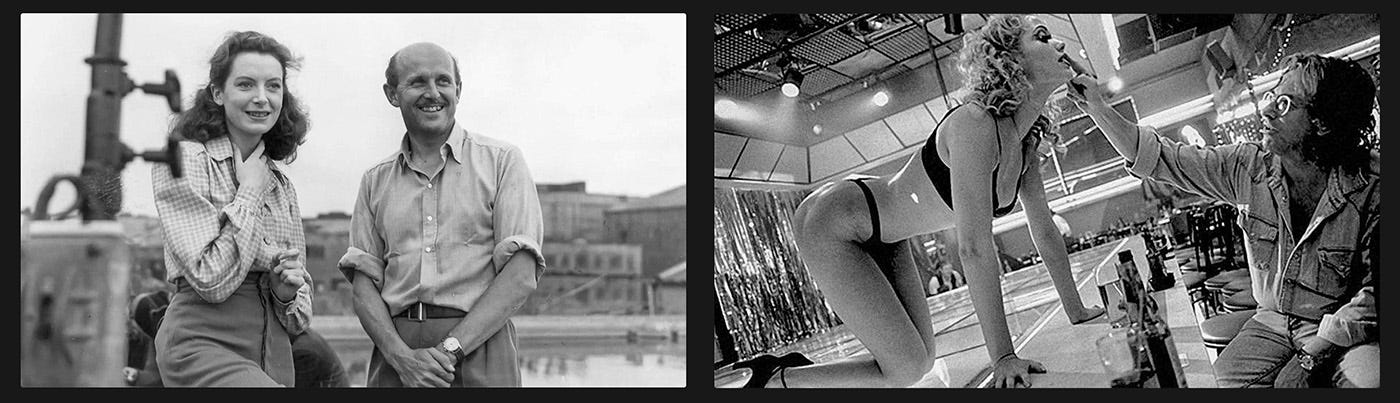

Behind the Curtain: The Real Drama

The parallels don’t just stop at the screen.

Black Narcissus was practically cast for tension. Kathleen Byron (Sister Ruth) was married director Michael Powell’s current mistress during filming. Deborah Kerr (Clodagh) was his recent ex — making his direction of both women simultaneously a Hitchcockian masterclass in purposefully mining offscreen melodrama.

Showgirls had its own blend of backstage drama: Eszterhas famously claimed in his autobiography that Berkley stayed in Verhoeven’s hotel room for the entire shoot, while Gina Gershon made no secret of her offscreen contempt. (To her credit, she’s still game to talk about it.)

It’s fitting. These are films built on volatile chemistry — on women sparring for visibility while men attempt to pull strings from behind the scenes.

The friction was real. The explosions, inevitable.

The Cast of Characters

For two films so wildly far apart in tone, era, and altitude, it’s frankly eerie how not just the four leads, but nearly every major character in one has a spiritual twin in the other — twisted reflections across the gender politics of their time.

From nuns and strippers to generals and gatekeepers, each is caught inside a system they believe they can outwit. And each fail.

So with nostalgic reverence — and a raised eyebrow — let’s chart the full ensemble of cinematic soulmates.

🎧 [PLAYBACK: SOUND ON]

Think of it as the opening credits of The Love Boat, just stormier. And with better lighting. So smash play on this campy disco remix of the schlocky 70s theme song and let’s set sail.

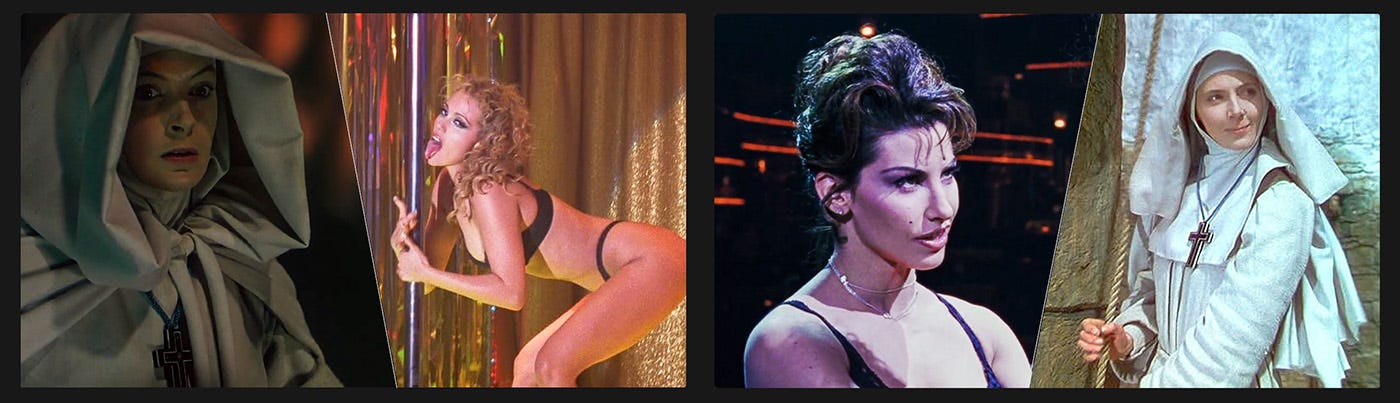

Sister Clodagh ⇄ Nomi Malone

Deborah Kerr | Elizabeth Berkeley

The Delusional Heroine

Newly anointed, fiercely ambitious, and deeply unmoored — Clodagh and Nomi both charge into unfamiliar terrain thinking they’re in control. Instead, they’re haunted by past trauma, seduced by power, and devoured by the very institutions they set out to conquer.

Each claws her way up a corrupt system built to exploit her, chasing a promised land that exists only in her imagination. Clodagh to spread God’s word through colonialist Third World infestation, Nomi to headline a topless casino musical drenched in capitalist misogyny.

Both seek reinvention in seductive, hostile environments. They begin with conviction and determination, but their headstrong self-importance unravels them.

Nomi’s hitched ride out of town directly echoes Clodagh’s descent from the mountain — forever changed, leaving tragedy in their wake. Their journeys end the same way: alone, wiser, bruised, but unbroken and left to fight another day.

What they ultimately find isn’t ascendance or transcendence. The scenery seduces them, swallows them whole, and then spits them out.

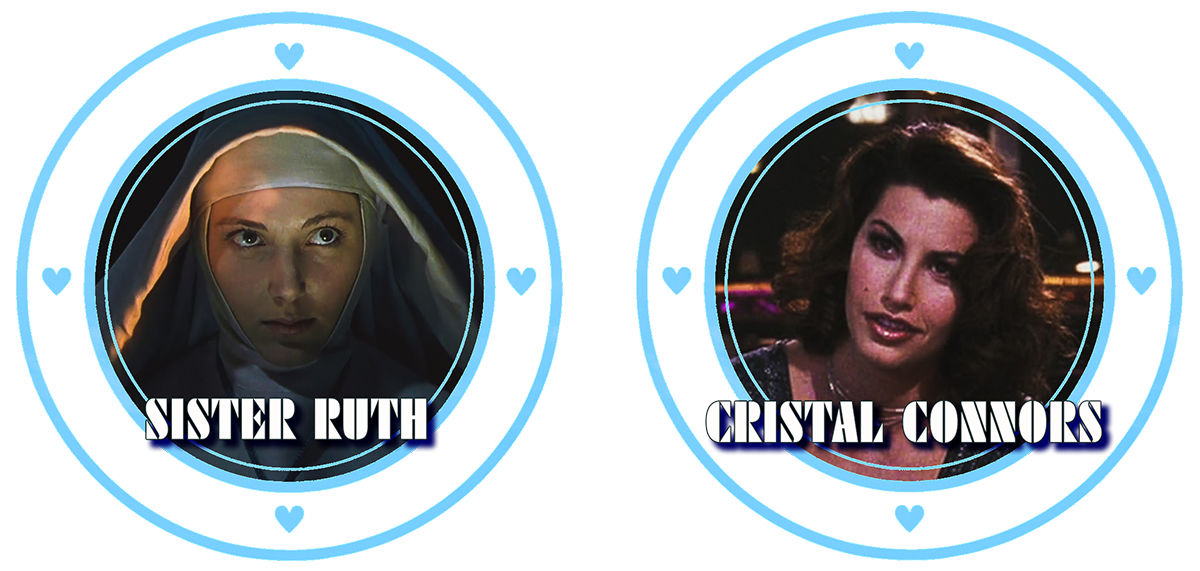

Sister Ruth ⇄ Cristal Connors

Kathleen Byron | Gina Gershon

The Woman on the Edge

Seductive, predatory, and burning with repressed desire. Ruth and Cristal are jaded women who see through the fantasy and lash out when they’re no longer centered. One casts off her habit and dares put on lipstick; the other autographs her headshots with it at Spago.

They’re magnetic, manipulative, and emotionally volatile — seductive foils and erotic rivals to our protagonists. They represent temptation, defiance, and the danger of not playing nice.

Each combusts under pressure, then falls — literally and figuratively — after challenging our lead. Ruth off a cliff. Cristal down the stairs. Just in time to realize the system has already chosen someone younger. And hungrier. For Doggie Chow.

They’re both villain and parable. Showing us what happens when power fades, when desire simmers too long, when the institution no longer has any use for you. And they go out knowing exactly why.

They’re also both *easily* the best part of either film.

Sister Philippa ⇄ Molly Abrams

Flora Robson | Gina Ravera

The Genuine Good Person

The lone gentle soul. The moral compass. The quietly gifted artisan of her world.

Philippa and Molly both care deeply, offering creativity and empathy to institutions that punish expression in favor of obedience and conformity. Whether as a gardener or a costume designer, both prove the most grounded among the whole ensemble.

Philippa is undone by the intoxicating beauty of Mopu’s surroundings. Molly is exploited and discarded in a grotesque final-act betrayal, one even Verhoeven and Eszterhas later admitted was a huge mistake. Her idea of beauty: a glammed-up rock messiah sporting a God complex with the hair to match. Both are pushed out not because they defied the system, but because they trusted it.

A reprieve from the power grabs and psychological spirals around them, Philippa and Molly represent the quiet tragedy of those who tried to nurture — and paid the price.

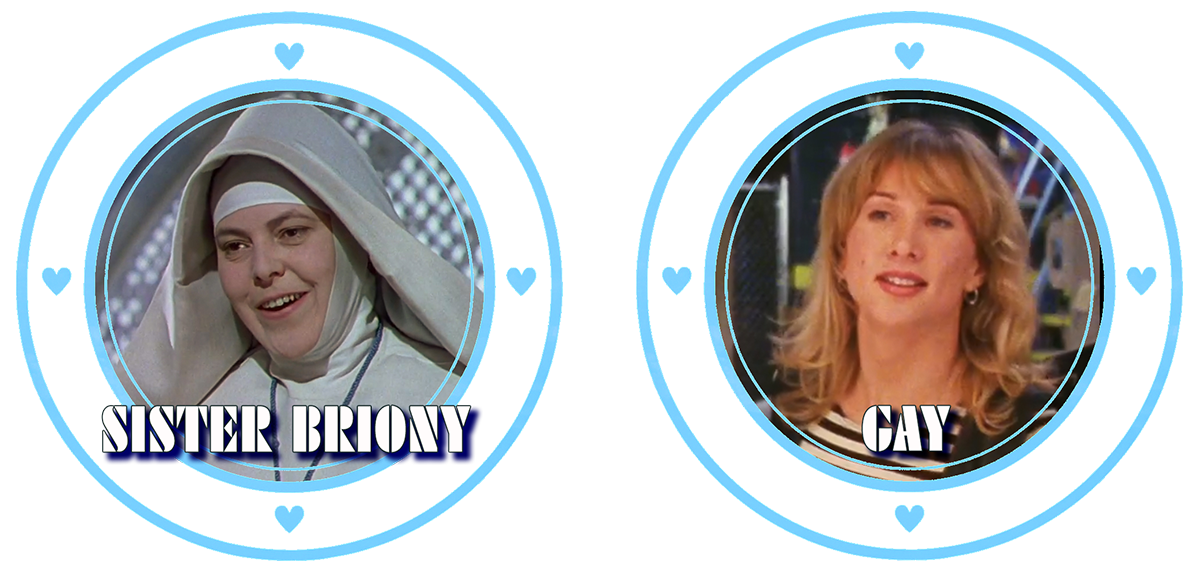

Sister Briony ⇄ Gay

Judith Furse | Michelle Johnston

The Rock

We know everyone wanted Briony to land as Mama Bazoom, ourselves included on first glance — but sorry, she’s Gay. And yes, with a capital “G.”

Sister Briony is the practical veteran whose brawn and no-nonsense attitude keeps the convent running. She’s not caught up in the psychodrama. Nor is she there for the spectacle. She rolls up her sleeves and gets things done.

Gay does the same backstage at the Stardust: part fixer, part den mother, all human fire extinguisher.

Neither is the star, but both are indispensable. They hold the place together while everyone else spirals. They know the machinery, respect it just enough to stay alive, but aren’t deluded by it.

And while Gay may not quite live up to her name, both Briony and the actress who played her brought unapologetic butch energy to the convent. You see it. You respect it. And you love them for it.

Sister Honey ⇄ Julie

Jenny Laird | Melissa Williams

The Sweet One …Until She Isn’t

Friendly, accommodating, and just a little bit manipulative.

Sister Honey and Julie are the sweet ones who are always watching, always waiting in the wings. They know how to weaponize likeability and reflect the illusion of sisterhood… until survival instinct kick in.

Both show that the system doesn’t just tear down the bold or defiant — it rewards quiet opportunism.

Honey’s compassion curdles under the pressure of caring for a critically ill infant. Julie’s pesky kids are verbally abused by the Mean Girl lead understudy backstage at the Stardust.

When pushed too far, both women decide someone has to go.

They’re nice. Until they’re not. And you never saw it coming — because you were too busy underestimating them.

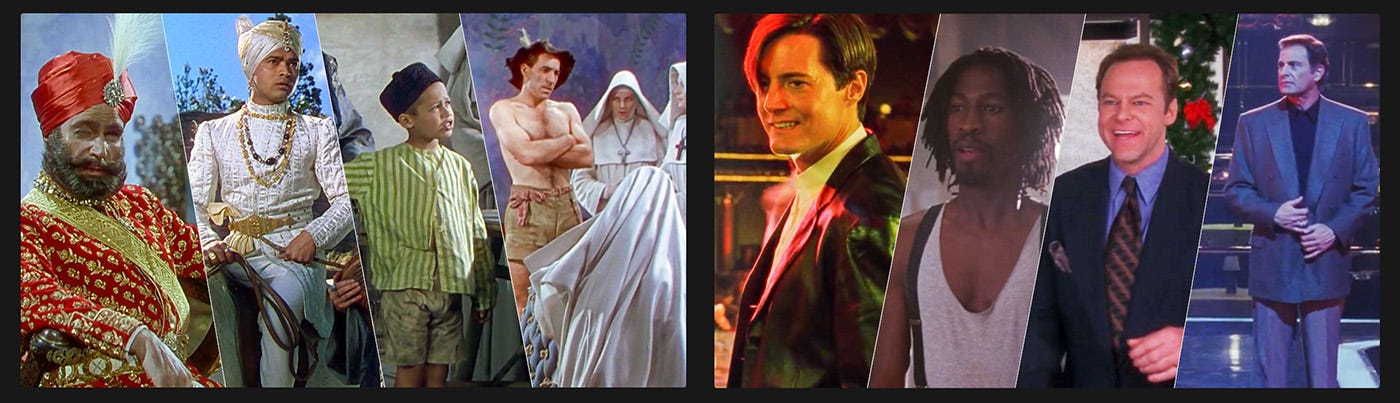

Mr. Dean ⇄ Zach Carey

David Farrar | Kyle MacLachlan

The Men Who Thought THEY Were the Plot

Mr. Dean starts out as Tony Moss — the crass, lascivious gatekeeper — but quickly morphs into Zack: the guy with just enough charm to think he matters more than he does.

Both are objects of desire and instigators of jealousy. They see the system for what it is, yet continue to profit from it.

Zach “likes” Nomi but won’t save her. Not when there’s money to be made. Mr. Dean grows to “respect” Sister Clodagh, though can’t help but savor her unraveling. He enjoys seeing the scourge of colonialism fall from the perch it never really earned — and her along with it. Zach’s smug condescention of Nomi emerges from the shadows when he finally discovers the sexual purity she offered was also just a facade hiding behind a lengthy hooking rap sheet.

They offer the illusion of support while reinforcing the very structures that devour our heroines. They want credit for being decent without giving up power.

They’re not the story. But they clearly want us to believe they are.

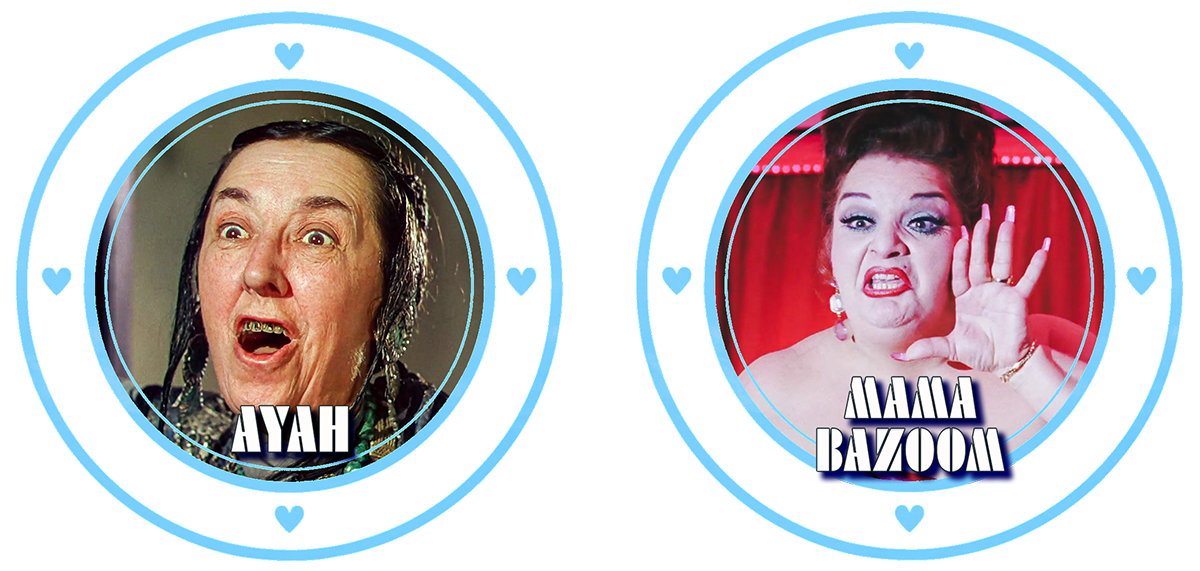

Ayah ⇄ Henrietta “Mama” Bazoom

May Hallatt | Lin Tucci

The “Old Broad” Who’s Seen It All

Costumed, kooky, and impossible to forget.

They burst from the margins with outsized personalities, bearing witness to the madness with bemused detachment — and a strong dose of camp.

One’s wrapped in tattered woolen shawls and matted braids, the other in sequins and hydraulically-powered brassieres.

Both Ayah and Mama know the fate of our protagonists the moment they arrive. They’ve seen dozens just like them come and go over the years: naïve, ambitious, doomed. They watch it unfold without flinching, because they’ve long since stopped buying the fantasy being sold.

Sardonic, unfiltered, and always a step ahead, they don’t beat around the bush. They’re never fooled for a moment… and refuse to pretend otherwise.

And that’s why they outlast everyone.

Kanchi ⇄ Penny a.k.a. “Hope”

Jean Simmons | Rena Riffel

The Erotic Scapegoat

At least we Hope she Kan. Sexualized innocence — used, discarded, and resented by other women not for what they do, but for what they represent.

Recipient of perhaps the least subtle character naming in the history of the Hays Code, Kanchi is a vessel of youthful eroticism introduced in the palace courtyard surrounded by a flock of cocks, a free-spirited distraction the sisters can neither control nor fully understand.

Penny is treated as a joke from the get-go — demeaned, renamed, and reshaped by the system until she’s docile enough to humiliate.

Both become catalysts for collapse, not by defiance, but simply by existing.

They aren’t threats because they act out. They’re threats because they remind others around them exactly of what they’ve repressed inside themselves.

Both get punished for it.

Joseph Anthony ⇄ James (Smith?!?)

Eddie Whaley Jr. | Glenn Plummer

The Truth Teller

Gregarious, kind, and impossibly earnest.

Joseph Anthony and James are the rare male characters in these films who aren’t trying to control the narrative. They’re translating it.

Joseph Anthony is literally a translator, bridging colonial arrogance and local reality with more precocious grace than the nuns deserve. James is a metaphorical one, trying to pull Nomi toward something that resembles self-awareness — away from the stage lights and into authenticity.

Both are wise but emotionally stunted. Joseph Anthony because of his youth. James because, well, his problems with a certain part of the female anatomy speak louder than his “wisdom.” They don’t belong in the systems they’re stuck inside and their honesty costs them.

Whether it’s Joseph Anthony informing the nuns of a baby’s death or James shouting “Everybody got AIDS and shit!”, they speak uncomfortable truths. And in these worlds, truth doesn’t get rewarded. It gets left behind.

The Old General ⇄ Tony Moss

Desmond Knight | Alan Rachins

The Gatekeeper with a Heart of Gold

Bombastic, theatrical, and utterly in love with themselves and their entitlement.

The Old General and Tony Moss are arrogant power brokers who command attention through sheer force of personality. One presides over a mountaintop palace; the other over a backstage cattle call. Both offer access to elite spaces, but only on their terms.

They don’t just guard the gate — they are the gate. And they revel in their own mythology.

The aloof royal and the sleazeball producer each adopt aggressive, performative cruelty. Old General wielding authority through hollow threats and imperial pomp, Tony through gleeful misogyny and insult-as-audition.

But beneath all the spectacle of holding court, they both offer misguided benevolence: The General gifts the nuns sausages while staring longingly at his own reflection in that ornate, ridiculously phallic wall mirror; Tony generously offers ice for nipples and cheap validation for broken dreams.

They’re stepping stones who mistake themselves for final bosses. And once our protagonist’s arc outgrows them, they largely vanish. (Too bad, ‘cause Alan Rachins was kinda awesome. R.I.P.)

The Young General ⇄ Phil Newkirk

Sabu | Greg Travis

The Ornament

Polished, smug, and completely useless.

The Young General and Phil Newkirk are ceremonial mascots of institutions that no longer have meaning, only momentum.

The Young General is the product of colonial pageantry, dressed up and paraded around for significance he doesn’t fully understand.

Phil is a corporate lackey posing as a PR exec — equal parts sycophant and pimp — whose real job is to keep the machinery running while pretending it’s glamorous.

Neither has real power, but both are complicit in upholding it. They flirt with status, bask in its glow, and indulge the perks. But when the story sharpens, they too disappear, because there’s nothing under the surface.

They’re losers and simply decor. But at least Powell and Pressburger didn’t graphically dismember Sabu in the opening moments of their next movie, as Verhoeven did to poor Phil.

Reverend Mother ⇄ Al Torres

Nancy Roberts | Robert Davi

The Unfiltered Voice of Reason

Both lead guilds of female workers — nuns or strippers — with the same air of managerial detachment and weathered authority. Their job isn’t to nurture; it’s to maintain order. And they’re damn good at it.

Reverend Mother doesn’t believe Clodagh is ready to lead, and she’s right. Al isn’t impressed when Nomi walks out to dance in Goddess instead of on his customers’ laps, and he’s right, too.

They’re the ones who’ve seen the cycle before, know how it ends, and are tasked with keeping the doors open either way.

They present as stewards of the “services” they provide, but they’re really caretakers of the Machine, overseeing and enabling the exploitation of others, whether via chastity or debasement.

Their concern only surfaces once the damage is done — when it’s safe to feign dignity and the stains left on our protagonists are someone else’s problem.

End Credits

So, there you have it.

A full cast of doubles, echoing across decades, continents, and the full spectrum of cinematic respectability.

One film drenched in Technicolor restraint, the other in neon excess — yet both arrive at the same emotional cliffside.

Maybe the scenery really does swallow them whole.

Or maybe we just like watching them fall.

Both, essential films.

Craving even more? Read SINephile’s full-length reviews of Black Narcissus and Showgirls.

Watched Black Narcissus after finding your post about Showgirls. Thoroughly enjoyed it, what a sumptuous film. You make a good case in comparing of the two!