SINephile's 100 Essential Films

Not a canon. Not a manifesto. Just the movies that built us.

Everyone’s got their own version of the greatest films ever made.

After finally plugging our viewing gaps from the now-infamous Sight & Sound list a few years ago, it only felt right to compile ours — not so much as a definitive canon, but as a roadmap.

These are the 100 narrative features that built us: the sacred, the profane, the incomparable. Some are revered classics. Some are personal obsessions. (Some, like Showgirls, are both.)

I skipped documentaries and experimental films for now (they deserve their own spotlight), aiming instead for a breadth of genres, decades, and countries — without losing sight of the stories that actually mean something to me.

Are the rankings precise?

Of course not, and they’re not attempting to be.

How do you weigh a Technicolor musical against New Hollywood grit or a screwball comedy against a war epic? You can’t.

So, here’s how we look at them…

Foundations of Obsession

Pictures that cracked open our imagination beyond the world of film.

Early encounters, first cinematic loves, the ones that made us realize movies could feel bigger than life — or smaller than a gasp of breath.

The 400 Blows (1959)

Cinema’s greatest coming-of-age story. Full stop.

Truffaut understood that rebellion could be both survival and art.

He redefined movies forever, helping kickstart the French New Wave, one of the medium’s most profound and lasting movements.

Its influence is absolutely everywhere today, both onscreen and off.L’Avventura (1960)

Antonioni perfects the anti-thriller.

An achingly gorgeous mystery where the real disappearance is meaning itself.

He deftly layers tension upon mystery only to playfully withhold the catharsis everyone expected as necessary to storytelling.

Sure, it plays glacially for some, but I’ve been obsessed with this picture ever since stumbling upon it when I first landed at Criterion.

(Mike White must’ve felt similarly, because the entirety of White Lotus: Season 2 was an expertly crafted homage.)

It also boasts one of the most fascinating origin stories in all of film history — one that’s coming soon to SINephile.Black Narcissus (1947)

A shockingly erotic, long-censored, anti-colonial allegory rendered in the most ravishing Technicolor ever committed to film.

The world-building that Powell & Pressburger crafted from the confines of the backlot at Pinewood Studios, London, in the 1940s, remains utterly astonishing and a feast for the senses.

Repressed desire, unchecked ambition, and unbridled jealousy arrive cliffside at a remote mountaintop convent in the Himalayas and invite us to watch along as entire power systems fall from the edge.Tokyo Story (1953)

The simplest plot, the deepest heartbreak.

Ozu’s masterpiece embodies the entirety of the human condition.

Its story is universal to anyone who’s ever been either parent or child. Hugely introspective and utterly gut-wrenching.

Even if you don’t nod in knowing agreement while watching, you sit still, feeling every quiet truth land like a sledgehammer to your sense of self.Ikiru (1952)

A civil servant builds a playground, and Kurosawa reminds us why life matters.

This titan of world cinema hand-down invented the modern action film throughout most of his storied career, through epics like Seven Samurai, The Hidden Fortress, and Ran.

So, it’s hugely ironic that perhaps his quietest picture is also his truest masterpiece.

Funny how that works.

The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928)

Falconetti delivers what many reasonably consider to be the greatest screen performance by any actor — ever.

Every twitch of the eye, every contortion of agony as she stands trial awaiting her fate, feels etched into celluloid with divine fire and brimstone.

Dreyer’s stark close-ups and stripped-down sets only magnify her impending martyrdom.

If you watch only one silent film in your entire life, let it be this one.Modern Times (1936)

Chaplin’s sharpest commentary on the interplay between industry, technology, alienation, and resilience, wrapped in slapstick perfection.

His iconic Tramp persona takes on the Machine and slyly wins simply by losing.

A devastating social critique blended with a ballet of comedic genius and choreographed factory gears.

Still uncomfortably relevant to today’s fears over AI.

When the phrase “Does it stand the test of time?” gets thrown around, this is what they’re talking about.Pather Panchali (1955)

Rural poverty and childhood wonder collide in Satyajit Ray's devastating, lyrical debut.

No first feature that I’m aware of seems more surprisingly accomplished.

It glides effortlessly between naturalism and visual poetry, documenting an Indian village child's joys and losses, inviting recognition and opening minds in ways few films by even long-established masters prove capable.

Quiet, rough-edged, and utterly luminous.Only Angels Have Wings (1939)

Hawks' perfect blend of adventure and chemistry.

He makes fatalism feel like flirtation as Cary Grant and his rag-tag crew of flyboys entertain Jean Arthur during an overnight cruise layover in a lively, yet precarious South American port.

A bar hangout film where death ominously circles like the atmospheric fog that invites it in.

Grant and Arthur crackle, but it's the undercurrent of unspoken code, of men who show love through action, not confession, that lingers long after landing.

A film that out-Casablancas Casablanca for me. Yes, really.The Third Man (1949)

A noir so rich it verges on operatic.

Tilted frames, dripping alleyways, sewer chases, and a zither score that shouldn’t work but does.

Welles looms like a myth before we even see him. And when he finally appears, it’s pure movie magic.

Vienna’s ruins have never felt more alive.

Director Carol Reed isn’t quite the household name today that he deserves to be (he shows up more than once on this list).

The Third Man proves just how ridiculous that oversight is.

The Conversation (1974)

Gene Hackman’s best performance and Francis Ford Coppola’s most meticulous film.

Wiretaps, surveillance, isolation.

Hackman’s haunted Harry Caul is a character who takes time to fully understand, which seems weird at first until we slowly realize that, inside, he’s actually all of us.

A slow burn of paranoia, guilt, and the terrifying realization that observation inherently changes the observed, whether they’re aware of it or not.

The echoes in our present-day social media surveillance state are downright eerie.The Wizard of Oz (1939)

Timeless, Technicolor escapism.

Every kid's first brush with cinematic magic. And nightmare fuel.

An allegory, a cautionary tale, a trauma response, and a musical, all wrapped in a ruby-slippered journey down the Yellow Brick Road.

No matter how many times you watch it, the transition from sepia Kansas to Oz hits like a house falling from the sky and lands just as hard.Seven Samurai (1954)

Kurosawa’s influence still radiates through cinema everywhere today.

Because he made a new blueprint for action and shared it with the world.

Every team-up, every siege, every last-stand shootout owes the master an eternal debt of gratitude.

Yet no imitation over the decades has approached the depth of class commentary, moral complexity, and raw cinematic momentum.

Few vibe this cleanly 70 years on.To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)

Gregory Peck, moral compass intact.

Maybe the greatest adaptation of American literature ever set to film.

Robert Mulligan visually reconstructs Harper Lee’s classic novel with such restrained reverence and grace that even its purity feels quietly radical today.

Peck’s performance is gravitas personified. A courtroom drama that daringly cross-examined the American conscience.Rear Window (1954)

Voyeurism never looked this stylish or sinister.

A film about watching and being watched.

As usual, Hitchcock makes paranoia pleasurable, then slowly, surreptitiously poisons the well.

Grace Kelly in satin, James Stewart in a cast, and a courtyard full of lives we shouldn’t be seeing.

The Master of Suspense turned the act of watching itself into a moral Rubik’s Cube and invited us all to have a go.

Breathless (1960)

Godard rewrote the rules of cool and never looked back.

The jump-cut that launched a thousand imitators, inventing a new kind of cinematic grammar.

All cigarettes and swindle, it’s a film that refuses to sit still, held together by sheer gusto and Anna Karina’s eyes.

Pre-Breathless, cinema was staid and mostly just conformed.

Afterward, it drew renewed attention, so clearly borrowed from Jean-Paul Belmondo’s signature swagger.Bicycle Thieves (1948)

Post-war realism at its finest. A film so simple, it’s devastating.

Vittorio De Sica strips away artifice to reveal the bruised dignity of survival.

One man, one bike, and the weight of an entire world rebuilding in the aftermath of complete devastation.

The final shot is often imitated because it redefined what cinematic heartbreak could look like.

And it is, btw, called Bicycle Thieves. Not the singular, “The Bicycle Thief,” as you may at times see online. We’ll provide the whole backstory as to why in Ctrl+Alt+Decode.Star Wars (1977)

Cultural monolith and escapism in its purest form. You know why it’s here.

But beyond the iconography and merchandising juggernaut is a primal story told with sincerity, scope, and just the right amount of matinee movie schlock.

Lucas admittedly cribbed from Kurosawa’s feudal Japan in Hidden Fortress, the adventures of Flash Gordon, and Joseph Campbell’s monomyth, all while concocting a galaxy where good and evil were defined for entire generations.

You may prefer the sequel, but this was the Foundation, and it’s indispensable.The Wages of Fear (1953)

Sweaty palms, existential dread, and the most nail-biting truck drive in film history.

Clouzot aims tension like a sadist, stretching anxiety beyond its breaking point.

The panic is palpable as we embed with two men hauling a payload of nitroglycerine, avatars of capitalistic exploitation, driving headfirst toward oblivion with nothing but a paycheck and their pride.

A terrifying masterstroke.Rebecca (1940)

Hitchcock's debut American feature also remains one of his best, a gothic romance dripping with paranoia and menace.

Joan Fontaine’s fear is practically weaponized, swallowed whole by the storied mansion of Manderlay, both in its creepy shadows and under caretaker Mrs. Danvers’ icy, penetrating gaze whenever she’s not fondling her long-dead former employer’s silk underwear.

Rebecca is both a ghost story and a masterclass in how fear is invoked simply through memory, silence, and withheld affection.

And it doesn’t hurt that Sir Lawrence was kinda hot.

The Rules of the Game (1939)

Renoir skewers the bourgeoisie with elegance and savagery.

The OG class satire, inspiring everything from La Ronde to Down and Out in Beverly Hills.

He does it all knowingly, not picking a side — just lays out the hypocrisies like cards on a table and lets civilization eat itself.

Understandably, generations of filmmakers continue to feast off it.Citizen Kane (1941)

The camera tricks, the time jumps, the hubris.

Not sure we have to proclaim it to be the Greatest Film of All Time (or even that there has to be just one). But, yes, it deserves its reputation.

Beyond Welles’ bravura, Kane is a devastating portrait of the American ego, eroding under the weight of ambition, longing, and snow-globe nostalgia.La Dolce Vita (1960)

Fellini's glittering, melancholic portrait of modern emptiness never loses either bite or beauty.

Every frame seduces, then deftly undercuts.

Paparazzi, parties, and spiritual decay. Fellini poetically predicted our fame-addicted present.On the Waterfront (1954)

Brando changed screen acting forever, and his heartfelt, vulnerable performance still hits like a gut punch.

Kazan’s everyman morality play surprisingly reveals its truest power in key silences like pauses and mumbles.

It’s one guy fighting against a broken system, but the damage is already done.Sunset Boulevard (1950)

The blueprint for not just every Hollywood self-elegy that followed, but dare we say, almost every damn movie since.

Poison-dipped dialogue, gothic wit, and Norma Desmond ready for her close-up.

Wilder exposed Tinseltown’s seedy underbelly and embalmed it for our permanent viewing pleasure.

An addictive noir horror show that makes it impossible to unsee its echoes in nearly everything that came after it.

Cinematic Earthquakes

Films that rewired our understanding of what cinema could be — whether through scope, structure, subjectivity, or sheer nerve.

Some are emotional sucker punches. Others just sneak up silently yet with purpose.

All the movies that came afterward hit differently than ever before.

Apocalypse Now (1979)

A descent into madness with napalm in the morning and Wagner overhead.

War never looked this operatic before or since.

A grueling labor of love where we see every drop of blood and bead of sweat. The jungle breathes, the river devours, and cinema emerges altered on the other side of it.2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

The purest distillation of film as symphonic experience.

Kubrick encapsulates the infinite nature of space in a way no one else has before or since.

Every cut, every silence is architecture.

A monolith of form that changed how we process images on screen.Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975)

Three hours of just daily routine and then... everything ruptures.

Akerman bent time and snapped both the art form and our expectations around it in half.Each gesture accumulates like tectonic pressure. We begin to notice the patterns disrupted. The eventual break is shocking in its stillness and inevitability.

For the full explainer of why this isn’t really the #1 Greatest Film of All Time, as Sight & Sound claims in the latest update of their famed once-per-decade poll, read Ctrl+Alt+Decode.

Essential film, to be sure — just not the greatest of all time.Rashomon (1950)

A bandit, a bride, a samurai, and four clashing testimonies.

Rashomon turned a simple forest crime into a philosophical reckoning, introducing Western audiences to Japanese cinema and forever complicating the idea of objectivity on screen.

In so doing, Kurosawa fractured truth and reshaped narrative storytelling forever.

With each story, trust erodes, and cinema becomes less about what happened, more about who gets to say what the truth really is…

Timely, huh?Moonlight (2016)

A triptych of identity, masculinity, and intimacy. Jenkins turns whispered moments into seismic shifts.

He allows the camera only to gently caress its subjects, but smartly never dares to intrude. A film that maps its characters from the inside out.

And the needle-drop of that final shot is the most graceful, devastating, layered homage to The 400 Blows ever. The meaning behind it elevates the picture to a whole new level, making those in the know instantly burst into tears.

One of the best films of the 2010s, second only perhaps to Parasite on the road to cinematic perfection.

PlayTime (1967)

Monsieur Hulot drifts through a Paris of grids and gadgetry.

The film’s immersive scale and choreographed humor remain unmatched: a ballet of the banal made grand.

Tati explodes modernity’s sterile perfection with a comedy of collapsing systems. Every frame is a blueprint built into an endlessly explorable funhouse.Metropolis (1927)

Fritz Lang’s towering vision of a future divided by privilege and power still feels eerily current.

Its iconic robot, monumental sets, and feverish politics forged the DNA of science fiction on screen.

Industrial might, class warfare, and German expressionist grandeur collide into one of cinema’s first cataclysmic precautionary warnings.Pulp Fiction (1994)

From Royale with Cheese to adrenaline shots to the Bonnie Situation, every scene became a reference point for pop culture.

The indie explosion of the ’90s simply wouldn’t have happened without it. And neither does half of your Letterboxd watchlist.

Tarantino reshuffled the deck *and* the timeline. Violent, verbose, and impossibly cool, it updated the stagnant manual on what movies could be.The Exorcist (1973)

The first horror film nominated for Best Picture (not to mention nine other Academy Awards).

Psycho couldn’t even pull that off. And it’s still rare even today.

Blending documentary-adjacent style with metaphysical terror, The Exorcist summoned both Catholic guilt and cinematic evolution.

While twisting heads, Friedkin also twisted expectations.Taxi Driver (1976)

Scorsese’s Travis Bickle was an uncomfortable mirror held up to America’s post-Vietnam psyche.

The film’s descent is slow, sweaty, and operatic, culminating in a crescendo of mythic violence.

An urban fever dream of loneliness, rage, and delusion.

Network (1976)

Sidney Lumet’s epic satire predicted the rise and dangers of infotainment with terrifying clarity, decades before his vision would be proven to everyone else.

Anchored by monologues that feel ripped straight from today’s headlines, Network saw the news industry’s descent into madness before the rest of us changed the channel.

He showed us the moment rage and confirmation bias would turn ratings gold.

That took social media algos forever to figure out… but once they did, it ripped our social fabric to shreds.The Night of the Hunter (1955)

With its surreal compositions and morality play tone, it first presents as a bedtime story until we realize it’s told by a lunatic preacher.

Robert Mitchum’s instantly recognizable “LOVE” and “HATE” tatted hands haunt cinema history and every director who’s ever tried to film a dream. Just ask Guillermo del Toro.

Renowned character actor Charles Laughton only directed one film, ever.

His gorgeous fever dream carved American folklore into nightmare-fuel that inspired countless contemporary auteurs.Raging Bull (1980)

Boxing is just the backdrop; the real fight is internal.

Daringly shot in searing black-and-white and edited like a symphony of violence, Raging Bull turned self-destruction into religious cinema.

Brutality as ballet. De Niro and Scorsese map out one man’s rage and playfully explore the limits of narrative storytelling for post-Golden Age Hollywood.Vertigo (1958)

Beneath its elegant noir surface lies a bottomless well of control, fantasy, and longing.

Vertigo wasn’t terribly well-understood for its time, despite rocking glorious visuals and pedigree.

But today, it’s seen as a master key to the subconscious mechanics of how the medium of film itself works.M (1931)

Fritz Lang’s ultimate masterpiece (and he had several) gave voice to the hunted and the monstrous alike, years before noir had a name.

With shadows, whistles, and Peter Lorre’s haunting presence, M turned manhunt into moral inquiry.

The birth of the psychological thriller — and the first film to put evil center stage.

Touch of Evil (1958)

A carnival of corruption where every shadow is secretly alive.

Charlton Heston, Janet Leigh, and Orson Welles orbit a world where the line between law and lawlessness dissolves into cigarette smoke and oil slicks.

Welles opens with one of cinema’s greatest long takes — homage beautifully paid upfront at the beginning of Altman’s Short Cuts (also on this list, only partly for that reason) — and then plunges into border-town sleaze.

The noir implosion, shot in firelight and filth.

Again, fascinating origin story and restoration history upcoming on SINephile.Blade Runner (1982)

The blend of neo-noir and sci-fi grandeur crafted a new template for decades of dystopian worlds to come after.

Its questions — about memory, humanity, and the cost of progress — linger as heavily as the film’s seemingly never-ending atmospheric downpour.

Cyberpunk prophecy soaked in rain and neon.

Scott’s masterpiece made the future look like poetry, and regardless of the number of cuts made to it over the years, we still can’t look away.Do the Right Thing (1989)

With its vivid colors, kinetic camera, and prophetic dialogue, it’s every bit as much a time capsule as it is a timeless cautionary tale.

The final confrontation lands like a brick through the front window of an entire nation that needed to wake the *ef* up.

A powder keg of race, rage, and refusal to abide by everyday injustice, Spike Lee made the block feel like the whole world.

Because it is.

As an exploration of distinctly American problems, it’s brilliant. But expanding upon that to encompass our common experience as a global species? Uhhh… mind blown.Psycho (1960)

From filmdom’s most famed shower scene, even more than half a century later, to Hermann’s screeching violins, Psycho turned horror into a cultural event that commanded lore-like warnings and vomit bags.

It’s the moment Hitchcock stopped toying with suspense as a repetitive, albeit highly effective trope, and started full-on weaponizing it.Again, an understanding of nuance is fully required here:

Hitch both cruelly exploited Perkins’ closeted off-screen sexuality and simultaneously elevated him to a household name for the purpose of crafting great cinema.

That’s neither entirely excusable nor completely commendable.

But, when you zoom out to judge the art itself… Psycho is essential cinema.

And his son, Oz, a talented horror director in his own right today, seems to agree.Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway, long before they robbed Moonlight of its deserved Oscar glory with the most epic gaffe in the ceremony’s history, turned outlaw romance into countercultural mythology.

The final slow-motion ambush remains one of cinema’s most brutal and beautiful farewells.Young, doomed, and bloodier than anything mainstream audiences had ever seen, the New Hollywood movement began in earnest with a gunshot that killed off the Hays Code.

The Color Purple (1985)

Anchored by Whoopi Goldberg’s powerhouse performance and writer Alice Walker’s epic scope, it’s a gorgeously world-building, deeply empathetic film that helped reshape what prestige cinema was even allowed to pull focus upon at the time.

This OG adaptation has received some criticism in later years over its slight dial back on the sexuality aspects of Walker’s novel, but that take is woefully revisionist. This was revolutionary cinema for the 1980s.

Only a filmmaker of Spielberg’s unforeseen influence and repetitively proven box office clout could’ve punched through the system in ‘85 to go as far as he did with its address of sexuality to mainstream audiences under the guise of a PG-13 rating. Unthinkable at the time.

The fact that Color Purple tied the all-time record for number of Oscar nominations (11) without scoring a single win is sickening in its brazen display of latent racism, misogyny, and homophobia… only to be echoed decades later in the coronation of Crash over Brokeback Mountain.

A painful, sweeping, ultimately triumphant portrait of Black womanhood in America.To Live (1994)

Zhang Yimou tracks one family’s quiet devastation in 20th-century China.

He’d single-handedly placed Chinese cinema on the world map with art house stunners like Red Sorghum and Raise the Red Lantern, then surreptitiously leveraged his newfound influence to indict the very power structure under which his entire society operated.

One of the most moving critiques of not just communism, but all authoritarian-imposed governance, ever committed to celluloid.

Won the Grand Prix at Cannes. Won the BAFTA for Non-English Language. Nominated by the Academy.

Banned in China — to this day. And yet he remains the country’s most celebrated film director for a reason. Made a ton of great films, but this is his masterpiece.Schindler’s List (1993)

Shot in stark black-and-white with the precision of a documentarian’s eye, it neither flinches nor sermonizes as Spielberg touches upon the Holocaust.

It simply records. And in doing so, Schindler repositioned the moral compass of how cinema as art can be leveraged.

Spielberg’s most soul-shattering achievement bears witness to a painful, shameful chapter in human history with no escape hatch to be found.The Battle of Algiers (1966)

Colonialism cracked wide open.

Shot like a newsreel, banned in multiple countries, taught in government coursework, and still studied by military tacticians around the globe, Battle of Algiers is both a historical artifact and a tinderbox of criticism unto itself.

An essential political film that feels like it’s still unfolding all around us.The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)

David Lean’s war epic is as every bit as psychologically layered as it is dynamically explosive.

What starts as an ordinary tale of survival is woven into a slow-burning study of ego, allegiance, and the absurdity of war’s moral calculus.

Lean blew up way more than just a bridge.

… Until We Did.

Films that felt immediately personal… and, over time, held up the mirror to something we hadn’t been ready to see in ourselves until, suddenly, we couldn’t look away.

This is where we feel what cinema does to us when it moves beyond admiration and into identity.

A Room with a View (1986)

What if the life we were told to want wasn’t the life we were built for?

This film handed us a question disguised as a love story — and dared us to answer it.

Btw, that pond scene? A few early realizations may have arrived alongside Rupert Graves, unannounced, but not unwelcome.

Brief Encounter (1945)

The heartbreak of timing never working out.

Many spend years chasing that same heartbreak portrayed throughout film history in everything from An Affair to Remember and When Harry Met Sally to Before Sunset and Moonlight.

But it all traces back here: the moment you realize love arrived — just not when it was allowed to.

Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974)

We don’t need subtitles to understand the looks they got.

Societal judgment on class, race, age, gender — uninvited, unavoidable, and best ignored as irrelevant.

Most of us have been there before. When something real doesn’t fit the script, and suddenly it feels like you’re the only one who sees the complexity and beautiful uniqueness of identity for what it really is.

This film didn’t have to overexplain life’s nuances to us. It just stayed with them, and so did we.

The Spirit of the Beehive (1973)

Many of us look back upon childhood as safe, innocent, even ordinary.

But this film made us feel otherwise.

It showed how kids quietly absorb grief and unease long before they know what either concept fully is or can put a name it.

And it left us wondering what else we might’ve sensed at that age, but never really understood.

The Life of Oharu (1952)

This was tragedy as both plot twist and slow fade into disappearance.

Oharu gets smaller and smaller until there's nothing left but silence.

We’d seen pain on screen before, but never quite this kind.

This was a shame you wear day after day until it just wears you down to nothing.

Talk to Her (2002)

Few films simultaneously feel both this intimate and this wrong.

It blurs love, control, and loneliness until tenderness and violation sit in the same frame as uncomfortable bedmates.

The discomfort Almodóvar made you feel was his whole design.

Most think of All About My Mother or Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown as Almodóvar’s career-defining work, but this is actually his most maturely crafted masterstroke.

Amadeus (1984)

We’re all Salieri.

Forman forged an elegant, addictively compelling, and sumptuously beautiful exploration of the inherent humanistic need for recognition.

Salieri knew exactly what he was hearing from Mozart and that he'd never even come close.

That kind of self-awareness in the proximity of genius humbles you, whether or not you’ve ever wanted it for yourself.

Close-Up (1990)

Ali was neither pretending nor intending to deceive. He was simply recreating his own shame just in order to be seen.

That‘s devastating on multiple layers.

Not just because we can see ourselves in him, but because we can recognize exactly what he was searching for through his quiet misdeeds.

To be understood, even if it’s just in the act of disappearing.

Short Cuts (1993)

Altman juggles a dozen unraveling lives in modern-day Los Angeles with such apparent ease, it’s simple to miss how brutal it all is.

This one made us see how damage caused by both action and inaction goes unnoticed — how often we’re hurting or being hurt, and no one’s really paying attention.

Far too often, including us.

Caché (2005)

Haneke’s hands-down best film sneakily backed us into a corner, turned off the lights, and asked us to confront ourselves in the darkened stillness.

A quiet reckoning with the mirror: what we choose not to see and who pays the price for our comfort in looking the other way.

It’s a collective, societal indictment. And it’s still happening all around us — every day and in every aspect of our lives.

Contact (1997)

Both sides believe they’re right: science and faith.

But Zemeckis’ greatest film put its finger on something far rarer: the ineffable human longing to search for meaning in a universe that may never answer us back.

And gives us the quiet hope that maybe there’s still an off chance that it somehow will.The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999)

We don’t have to be the anti-hero of our own narrative like Ripley is, but we can all recognize some aspect of the agony he felt.

The kind that festers when being on the outside becomes an exhausting, soul-dampening, full-time performance.

It’s gorgeous. It’s queasy. It’s impossibly seductive.

And it’s Cate Blanchett, thinking she’s in the love story — when sadly, she’s just the alibi.Rope (1948)

Audiences were drawn in by the camera gimmick, but weirdly hooked by something most couldn’t put their fingers on yet.

It’s a stylish stunt, to be sure, but under all that elite smugness and moral gamesmanship, we felt something else.

It was queerness cloaked in shadows and perfect posture, all weaponized by an impish Hitchcock cruelly mining the closeted sexuality of his two lead actors.

And yeah, we may’ve had a thing for Farley Granger, whether he actually choked that chicken or not.The Fallen Idol (1948)

Perhaps Carol Reed’s most unsung masterstroke.

His quiet mystery about innocence lost was just a narrative wrapper for exposing a universal truth.

A child watches adults lie, and in the process, their entire world falls apart.

Reed highlights that trust is neither immutable nor guaranteed — unguarded, it can easily slip away.

And getting it back once lost can prove impossible.Defending Your Life (1991)

It plays like a bittersweet comedy about the afterlife, but it hits like a thousand-pound dare.

This wasn’t just about Daniel being judged in the afterlife. Defending Your Life explores the process of building one’s personal philosophy for living a fully realized life.

You don’t wait around to feel brave or hope the things you want out of life to come your way. You act, or you miss your chance.

And no one’s keeping score but you.

Victor/Victoria (1982)

At first, many are understandably surprised why this hits so hard, especially if they aren’t a fan of musicals.

But Edward's richly realized art-deco Paris, Andrews' velvety voice, and that bodyguard needledrop made us feel something we couldn’t quite put into words.

Lesley Ann Warren still slays every time.

This one’s for the misfits of any stripe.Parasite (2019)

We expected sharp class critique from Bong. We didn’t expect to find ourselves so artfully portrayed in both families at once.

The same fears, same instincts — just different addresses, altitudes, and square footage.

It wasn’t just rich vs. poor. It was the systems that keep us locked into our given roles, blind to each other’s lives, and to the quiet desperation of wanting to be seen.

There’s a reason it became the first non-English language film to win the Academy Award for Best Picture.

Simply put: the most perfect film of the 2010s.Dr. Strangelove (1964)

You think it’s all satire until you realize the fate of the world hinges on a missed phone call and a d*ck joke.

It’s the kind of laughter that gets stuck in your throat, because the absurdity isn’t funny when you realize that it’s real.

Kubrick forces us to see how easily we can laugh at our catastrophic communal fate... until it’s too late to stop it.8 ½ (1963)

At first, it all just seems like nonsense.

Then we slowly realize that we’re watching ourselves: caught in the dance of denial.

Performing, directing, narrating — doing everything but fully existing.

Fellini asks us to see how easy it is to build a life without ever really living it.The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956)

Personally, it was my first Hitchcock.

I was the boy’s age, stuck inside during a hurricane, watching his parents scramble across countries to save him.

I didn’t entirely understand what it meant to be protected until I saw them push past their perceived limits, doing whatever it took to get him back.

Protection is about love overcoming vulnerability and taking you to places you never thought you’d go.

The Shawshank Redemption (1994)

Hope is key to human survival.

King and Darabont made us realize that dignity isn’t a luxury — it’s what keeps you alive when everything else falls away.

It’s how you actually manage to retain your humanity even when the walls start to close in.Stand By Me (1986)

Reiner’s film adaptation of King was never really about “the body,” per se.

It was about that moment when you realize you’re growing up laughing alongside lifelong friends both onscreen and off.

A film that magically makes us feel like we’ve aged and matured with its characters by the time the tears flow and credits roll.

And the fact that it was later mirrored in real-life tragedy turns the picture all the more gut-wrenching.The Lost Boys (1987)

Kiefer in a platinum mullet. Billy Wirth in fangs.

Sexuality and danger dance together in the pale moonlight and ask us to feel the draw of both.

Easily Joel Schumacher’s most accomplished film, Lost Boys promised freedom to an entire generation — or at least a cooler leather jacket and a stuffed beaver shoved in the closet behind the poster of a half-naked Rob Lowe.Le Grand Bleu / The Big Blue (1988)

The beauty grasps us first. Then the longing follows.

This was the film that seeded our wanderlust — before we even knew the word. Personally, it’s why I became a diver. It's certainly why I've traveled to over 80 countries over the years.

Much like L’Avventura at the top of this list, Big Blue was a direct inspiration for Season 2 of The White Lotus — filmed at the exact same locations.

Utterly fascinating origin story and journey into the canon. Coming your way soon on SINephile.

Some part of me at times still wants to vanish into water that impossibly blue.The Goonies (1985)

Mikey never stopped believing. Many of us did.

Watching it now feels like grief for the part of us that thought idealism could actually win.

Especially knowing most grown-ups long since traded their childhood wonder for 24-hour news cycles, social media rage machines, and the bizarre comfort many find in staying collectively scared.

But regardless of age, there's still a part of us that misses that belief — and maybe even a part that still wants to believe it can win.

The Glorious Contradictions

Highbrow meets lowbrow. Prestige Oscar bait crashes into pop trash.

These are the films that define what we ineffably love about cinema. They also mark why we started SINephile in the first place.

Because greatness in film isn’t just about taste. It’s about impact. The SINemeter speaks to that.

If even the most ardent of self-professed cinephiles can’t appreciate this last segment… well, you’re just missing out on so much joy.

And, before film became industry, isn’t that what it was all supposed to be about?

Showgirls (1995)

The Queen of Camp.

No film was mocked more savagely, or proved itself more worthy of redemption.An unholy fusion of All About Eve, Flashdance, and a crack’d coke mirror, Showgirls knows exactly what it’s doing — satirically torching the toxic confluence of misogyny and capitalism.

It’s beautiful, hateful, operatic, trashy, cruel, stupid, smart.

And the absurdity of that pool scene is one for the record books.Fargo (1994)

An uncomfortably polite descent into brutality.

The Coens’ true-crime fable finds tragedy in small talk and comedy in corpses, spinning moral rot and Midwestern manners into something oddly touching.

It's both the best and worst of America — with a wood chipper, a duck stamp, and Frances McDormand standing calmly between them.Serial Mom (1994)

Beneath the pastels and pearls lies pure, unadulterated rage.

John Waters gives us “Stepford Wife-as-serial killer,” gleefully impaling the hypocrisy of ‘90s suburbia — and the bloodlust of those performatively pretending to be shocked.

This is courtroom drama as tabloid slasher, and it’s not guilty of anything except being the most fun we’ve ever had watching someone murder a VHS unrewinder with a leg of lamb.Tootsie (1982)

A tonally pitch-perfect ‘80s comedy that only deepens with time.

Yes, it’s about a man in drag learning empathy for the experience of being a woman.

But it’s also about actors as parasites, power as seduction, and identity as performance.

Somehow, amid all the trickery, it’s still genuinely romantic. Somehow, it still works.

Oddly, alongside Jaws, Tootsie is one of only two post-Golden Age of Hollywood features that today’s titans of cinema most frequently acknowledge as profound historical influences on their work.Diabolique (1955)

French, foul, and fabulous.

This is horror as elegance — shot like noir, paced like a heart attack.

Before Hitchcock stole its thunder (and even its twist structure), Clouzot’s classic had already mastered the art of sick suspense: a cheating wife, an ice-cold mistress, and a body that refuses to stay dead.

Dirty water never looked this batheable.

Ed Wood (1993)

Tim Burton’s hands-down best film is ironically about someone who never made a good one.

A deeply sincere love letter to delusion, resilience, and the handmade magic of B-movie dreams.

It elevates the real-life, gender-non-conforming pulp director of infamous mid-century bombs into something close to a secular saint, without ever losing sight of the angora.

It’s camp as reverence, and that’s a contradiction we’ll always believe in.The Mother and the Whore (1973)

Three hours of talk, chain-smoking, and emotional gridlock, all scored to the rhythm of post-’68 hangover.

It shouldn’t work. It barely does. But it captures the ache of existential longing with a kind of accidental ferocity.

Fascinating distribution history and ride into the canon, too.

A film that flirts with nihilism, then dares to bare its bruised, bleeding heart before the credits roll.The Thing (1982)

No one trusted it in ’82. Critics pounced and audiences shrugged, resulting in box office disappointment.

Too gross, too cynical, too cold.

But Carpenter’s masterpiece has aged with perfection as one of the most frightening and enduring metaphors for paranoia, masculinity, and identity.

It’s gore as philosophy. Suspicion as style.

And still cooler than most “serious” horror films that tried way harder.

The blood test scene still gets us Every. Single. Time.The Great Dictator (1940)

The fact that Chaplin pulled off a Hitler parody before the U.S. even entered the war is wild enough.

But what makes it truly sing is the sincerity he gamely tucked inside the satire.

The speech at the end has been imitated to death, and yet, when you watch it in context, it slaps.

Idealism weaponized. A clown show with something real to say.

And timelier than ever.Drop Dead Gorgeous (1999)

As if Heathers went to the Mall of America, hitched a ride with Christopher Guest, and spent a week blackout drunk watching Dateline NBC.

Upon release, it was cast aside as mean-spirited.

Now it’s a bona fide cult classic satire, thankfully recognized by all but the most clueless as playfully designed to offend. And if it doesn’t, congrats, you’re part of the joke.

Beauty pageants, exploding teenagers, and small-town desperation — all served up deadpan with Aqua Net and a side of lutefisk.

Beverly Hills Cop (1984)

A fish-out-of-water action/comedy where the protagonist is smarter, funnier, and more morally grounded than anyone.

Murphy’s Axel Foley is all instinct and improvisation, turning Detroit hustle into a Swiss Army knife of justice wrapped in synthesizer, swagger, and banana-in-the-tailpipe irreverence.

The resulting combo in Martin Brest’s original was so magical, it makes the existence of the pathetic third installment all the more tragic.Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

Saturday afternoon matinee thrills sculpted with Old Hollywood gravitas that’s simply no longer possible to achieve or even properly mimic anymore.

It's cinematic theology in a leather jacket — sacred relics, fascist face-melting, and yet somehow still a first-date popcorn movie.

Harrison Ford played so many iconic characters throughout his career, but to us, he’ll always just be Indy.Die Hard (1988)

The blue-collar action flick that rewrote how vulnerability plays on-screen.

John McClane limps through glass, wisecracks through trauma, and makes masculinity more complicated and fun.

It’s violence as therapy meets terrorism as marriage counseling.

And Christmas Movie incarnate.Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982)

A space opera with Shakespearean soul.

This midlife crisis dressed in naval uniforms, literary quotations, and cold fusion has Kirk confronting mortality, mentorship, and regret, while the film boldly goes for gut-punches over phasers.

Few genre films explore humanity this earnestly.Jaws (1975)

A trashy dimestore novel elevated with orchestral terror and Spielbergian awe.

Yes, it's about a shark, but also about the cracks in every institution meant to protect us. Hammy in structure, poetry in rhythm.

Spielberg has since rightfully lamented the ecological fallout of falsely demonizing a crucial link in our ecological chain, instilling largely irrational fear (5-6 deaths annually worldwide, folks) that’s since helped push many species of the fish, including great whites, toward the brink of extinction.

But what he and composer John Williams accomplished here simply through a single sound cue and knowing when *not* to display the goods, showed near unparalleled inventive genius.

Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971)

A morality play dipped in Technicolor and LSD.

Gene Wilder’s Wonka is equal parts dreamweaver and nihilist, rewarding goodness but punishing gluttony, pride, and TV addiction with a wink and a flute fetish.

Childhood fantasy, yes, but with the logic of a parable and the pathos of a sick fever dream.

Wilder was right to only agree to the role if he could rewrite his titular character’s on-screen entrance. Subtly brilliant.The War of the Roses (1989)

Marriage as mutually assured destruction.

DeVito directs this operatic screwball farce like a Greek tragedy in a McMansion, as Kathleen Turner and Michael Douglas weaponize domesticity.

Love curdled into litigation, gourmet dinner parties into guerrilla warfare. No one wins, but it’s utterly delicious to watch them try.

DeVito was always underappreciated for his directorial talent, but this is him at his best.Ratatouille (2007)

The rat cooks, but the real miracle is that the critic is moved.

A Pixar fable about unlikely talent and the joy of making art in a world that prefers gatekeeping.

Its most subversive act is arguing that even a bitter palate can be redeemed by something beautiful — even simple — done really well.

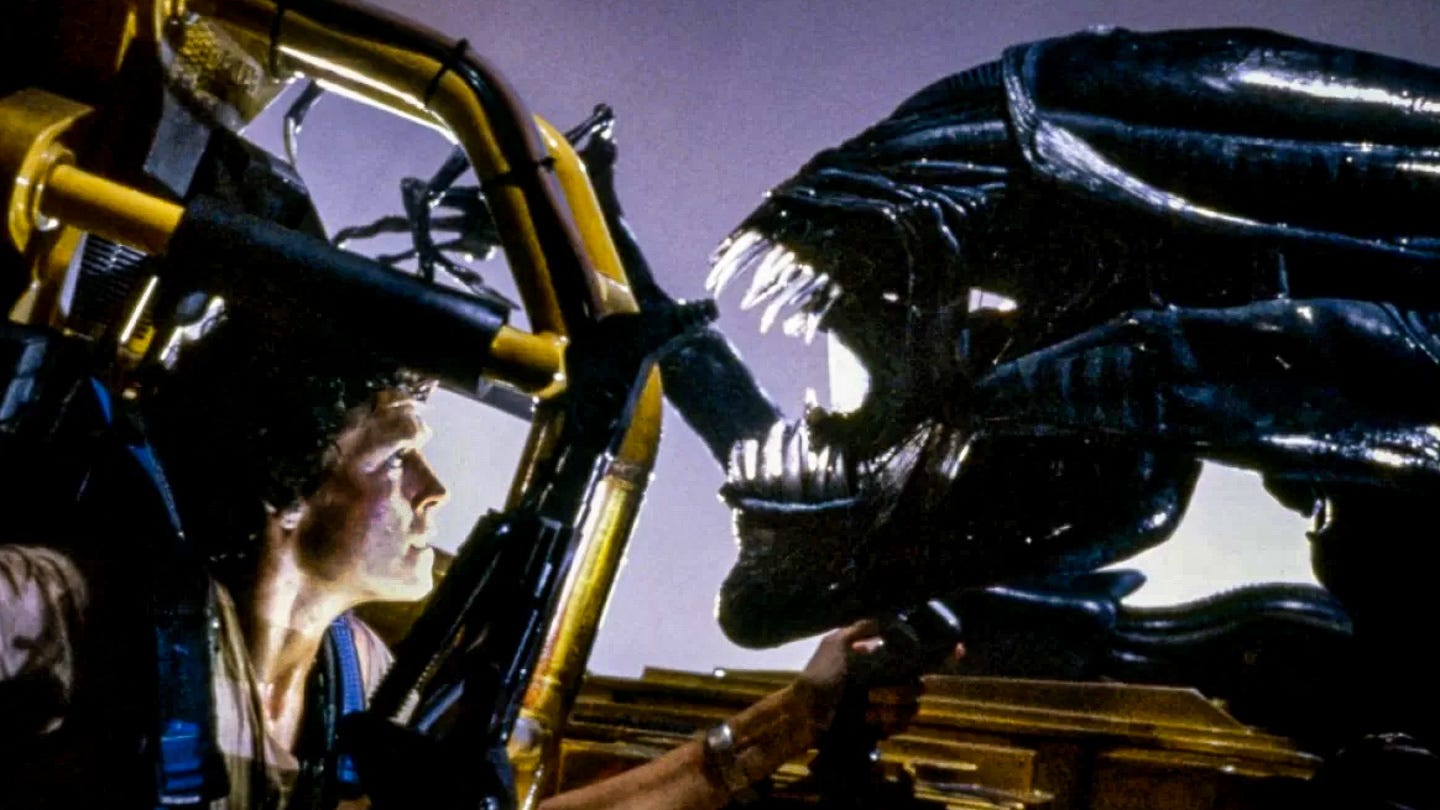

Sort of like these Glorious Contradictions.Aliens (1986)

Yes, the sequel.

What begins as survival horror becomes a meditation on maternal instinct and militarized panic.

Ripley returns to LV-426 to fight, to rescue, to reclaim, and to protect.

Ridley Scott’s OG expertly crafted the suspenseful setup. But Cameron creatively merged genres, adding firepower, velocity, and unprecedented brutality for mainstream cinema, while somehow never sacrificing heart.

Beneath all the pulse rifles: a lullaby.Near Dark (1987)

The western and the vampire movie drive into each other at dawn.

Kathyrn Bigelow’s dust-and-blood romance finds poetry in addiction, violence, and the alienation of being perceived as a societal outsider.

It’s too tender to be a horror film, too brutal to be a love story, but that’s exactly the point.

And who knew Adrian Pasdar would look that good as a blond?

Point Break (1991)

Zen crime.

The surfing-as-spirituality, bank-robbing-as-bromance we didn’t know we needed.

Bigelow returns (she was on a roll…) with what should be pure testosterone into a tender, mythic pursuit between soulmates on opposite sides of a line neither believes in.Boogie Nights (1997)

The rise and crash of a found family in the disco-lit trenches of the ‘70s porn industry.

Paul Thomas Anderson makes you laugh at their delusion and weep at their dignity, then empathetically offers them a second chance.

Ebert once called Anderson’s suspense work on display in key sequences the best since Hitchcock — not hyperbole.

It’s an elegy wrapped in a party, a cautionary tale pulsing with compassion.Starship Troopers (1997)

“Would you like to know more?”

Alongside Network, earlier on this list, one of the most eerily prescient satires ever constructed, disguised as a propaganda film, wrapped inside a teen soap, packaged as sci-fi spectacle.

Verhoeven weaponizes irony so thoroughly that an entire generation missed the joke — and in doing so, they proved the film’s point.Young Frankenstein (1974)

A perfect parody that gamely becomes the very thing it’s mocking.

Mel Brooks brings reverence to ridicule, honoring the OG master James Whale’s legacy while making us giggle at flatulence and tap dancing.

Somehow, it’s alive with pathos, romance, and the sheer joy of making movies.Matinee (1993)

A small film about absolutely everything: Cold War anxiety, sexual awakening, parental absence, and the way movies give us courage.

Joe Dante’s ode to William Castle and teenage terror feels like the antidote to today’s warranted cynicism, one cardboard atomic ant at a time.

A fitting bookend to this list, as a love letter to cinema itself.

That’s the show, my friend. 100 essentials.

A few masterpieces, a few underdogs, and plenty that don’t fit into neat categories.

Because neither do we.

If these films prove anything, it’s that greatness isn’t about consistency. It’s about conviction.

These are the ones that made us laugh, gasp, and hurt to become a part of who we are. And we hope they also cause you to feel, because that’s the power of cinema.

Thanks for staying for the whole retrospective, and make sure to share what else you think makes for essential viewing.