What's the Greatest Film of All Time?

It ain't Jeanne Dielman. And not for the reasons you think.

Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles has been deemed the #1 film of all time — according to the world’s most renowned movie poll that ironically never actually asked that question… to anyone.

Understandably, almost everyone thinks it did.

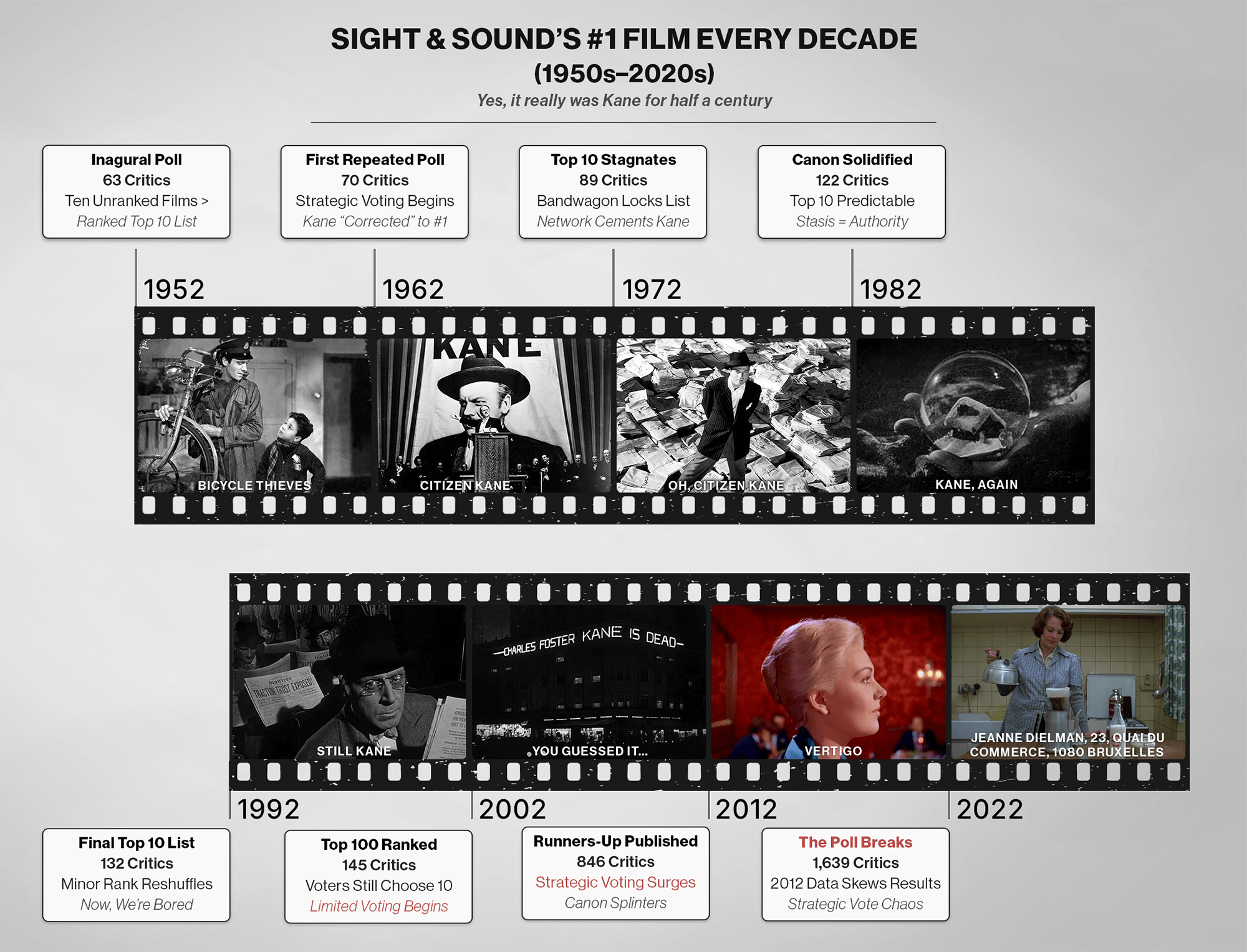

Since 1952, and only once per decade thereafter, Sight & Sound — the magazine of the British Film Institute — has released its definitive canon: a survey-based, industry-led ranking of the 100 Greatest Films of All Time.

Roger Ebert called it “by far the most respected of the countless polls of great movies — the only one most serious movie people take seriously.” He even credited its existence as a formative influence on his decision to become a film critic, and later built entire class curricula around its Top 10.

So when this decade’s results were announced, cinephiles and casual readers alike were left slack-jawed. A film most of the public had never even heard of — let alone seen — had taken the top spot, dethroning longtime champions like Citizen Kane and, most recently, Vertigo.

The new crown jewel? A 3.5-hour, nearly-silent study of a woman peeling potatoes in her kitchen.

But the outrage that ensued was misplaced. The problem wasn’t the film (which is indeed great). It was the framing. Few understood how the list was assembled — or what it even really measured.

Rather than offering an authoritative statement on what constitutes “great cinema,” the 2020s poll played more like a masterclass in how easily research design can collapse under its own good intentions to hilarious results. Dielman’s surprise ascent was just one symptom, among many, exposing a far deeper methodological disaster.

So here’s the thing: “The Greatest Film of All Time”?

Despite Sight & Sound claiming they have the answer, that’s not really what their poll says… at all.

Let me explain.

This Wasn’t a Conspiracy. It’s a Broken System.

I, too, have long championed the Sight & Sound list — ever since I was fresh out of college and working at The Criterion Collection.

Instead of relying on one editor’s whimsical opinion or even just anwers to a Buzzfeed quiz, it’s one of the only film rankings that even attempts to aggregate the insights of critics, historians, theorists and filmmakers across generations and points on the globe. I credit it with introducing me to many essential works I might've otherwise missed over the years.

So when I say that the 2022 poll was fundamentally flawed, I say it with reverence and measured affection. But also exasperation at the predictability of the ways in which increasingly bad survey design has corrupted it beyond recognition or resolve.

The problem isn’t at all specific to Jeanne Dielman. It’s the illusion that the poll is telling us what voters collectively believe is the best film of all time.

It doesn’t. It can’t. And it hasn’t been able to do so for awhile.

The survey methodology has been degrading for decades. And, in 2022, it finally fully collapsed.

How the Poll Actually Works

Everyone knows by now that polling isn’t an exact science, every method introduces some measure of unintended bias.

But the Sight & Sound poll is particularly jacked, and it became this way organically over time — not by purposeful design.

S&S asks participants to name their ten “greatest films of all time,” unranked.

That might sound trivial, but it means the poll operates on an “equal-weight, open ballot system.” Every film listed, among countless options available, scores a single point, regardless of whether it was a voter’s #1 or their #10.

That structure becomes precarious in a “repeated poll,” like this one. Voters the next time around don’t arrive blind; they enter with full knowledge of the last poll’s results and, in many cases, a quiet agenda to influence what comes next.

This immediately invites two problems:

Bandwagon effects, where prior winners stay winners simply because they’ve always been there.

Strategic voting, whereby participants game the system by boosting underrepresented choices — or promoting titles they think are ranked too low or might otherwise fall off.

So when the Sight & Sound editors take that unranked, strategicly assembled, raw ballot data of Top 10s and turn it into a stack-ranked Top 100 (or, god forbid, 250) list, the numbers aren’t telling you at all what they pretend to tell you.

That full list doesn’t resemble consensus anymore. At this point, it’s just elevated noise.

So how did a list meant to reflect global cinematic opinion become so easy to distort?

Let’s have some fun with the art of statistics and break down the flawed design choices — one rotten onion layer at a time.

Polling Bias Bingo Card

Network & Snowball Sampling

Rather than using a randomized or broadly representative sample of film experts, Sight & Sound relies on an in-house editorial nomination process.

This means new voters are invited by the same institution that shaped previous polls — projecting the biases of the curators forward.

In fairness, S&S has always been transparent about this, and while it was once the most prominent critique of the poll during decades when the participant pool was far smaller, it's no longer anywhere near the most damaging.Equal-Weight, Open Ballot Voting

Since 1952, voters list ten unranked movies from all of film history.

Each entry counts equally, regardless of whether it was a passionate #1 or near afterthought. A film appearing tenth on 100 ballots still beats one appearing first on 99.

This system behaves an awful lot like Approval Voting — think Rotten Tomatoes — only with an open, infinite nomination pool. It flattens voter intent, favors consensus picks, and rewards strategy over informed opinion.Repeated Survey Effects

Every ten years, the same well-informed voter pool returns (each time, expanded) — armed with a full history of past results, including an extended, ordered list of the 150 runners-up who didn’t quite make the cut the last go-around.

This turns the poll into an endless feedback loop.

Voters know exactly what was snubbed and what’s hovering near the cutoff, nudging future ballots toward "fixing" those perceived oversights.

The result is less discovery, more editorializing.Limited Input, Unlimited Output

Voters supply ten titles.

S&S extrapolates a Top 100 — and even a Top 250.

That’s a massive interpretive leap from such a small data sample.

Voters with only 10 precious votes, aware of this disconnect, make tactical choices: omitting “safe” films from the prior list, boosting vulnerable ones or those they think should rise in rank.

Multiply that behavior to absurd proportions, and the final list starts to look less like a democratic snapshot and more like a coordinated chess game flipped upside down in frustration.Stack-Ranked Results

The final product is a ranked list, even though voters can’t rank their choices.

This presents the illusion of mathematical authority, yet it's all built on top of unranked, strategically-assembled ballots.

This disconnect didn’t matter much when only a Top 10 was published for the first fifty years — not as statistically sound as collecting ranked lists from the start, but also not terrible.

Once S&S began inflating the output to a Top 100 at the turn of the century, the underlying system couldn’t bear the weight of the ensuing effects and the whole thing eventually collapsed.

The Death Cyle of a Poll

The first two methodologies in the Bingo Card above introduced flaws inherent in the poll's design since its inception over 70 years ago, but at least those were manageable.

"Repeated Survey" obviously wasn't a vector until the second poll in 1962. But even by that early point the effects were made clear, with voters “correcting” the #1 from the first list, Bicycle Thieves, to the “safer,” Hollywood-centric consensus pick Citizen Kane.

The problems were far less apparent in the results until 2002, before which S&S only published the Top 10 Greatest Films of All Time. Everything changed that year when they decided to expand to a "Top 100" list — understandably, to break the catharsis of a largely static list with Citizen Kane cemented at the top for decades.

The critical mistake was that they kept the same survey design asking for unranked "Top 10" lists thereafter, at which point they shifted from simply equal-weight, open balloting to an extremely problematic hybrid with “Limited Voting.”

The breaking point came in 2002 with that change, but the effects on that decade’s list were still rather contained because voters were neither aware that a Top 100 was being compiled from their limited ballots of ten entries, nor had they seen the 90 runners’ up from any of the prior polls that didn’t make the cut.

Sight & Sound then fractured their methodology even further in 2012, when the "repeated survey" vector kicked back in, since voters had seen prior results for a complete Top 100 at that point, and would, for the first time, use their now-”Limited Voting” capacity of still compiling Top 10s to influence the broader list results to the extent they could via "strategic voting."

Sadly, they broke the poll yet again when they began releasing the 150 runners-up list beginning in 2012. The availability of this historical, behind-the-curtain info to voters in 2022 encouraged an unintentional pile-on effect whereby "strategic voting" targets specific entries to push them over the line and onto the Top 100.

With each breakage, compounded by evermore participants armed with only 10 votes, the methodology introduced an unmanageable amount of noise, and the results got more and more skewed and non-sensical.

In this now-grotesquely Frankesteined polling methodolgy, it’s illogical to assume people won't engage in strategic voting to stretch their influence. Regrettably, those who don't vote that way are penalized in this system because, while they may be more honest in their answers, if they choose films not already on the prior Top 250, they're throwing their vote away for the final list.

So, in design, the system rewards strategic voting, wildly skewing results, even worse in a repeated poll in which voters know the prior results. As of the 2020s, the rankings may have turned Looney Tunes. But, as of 2012, all bets were already off.

What you're left with is a canon built on distorted math and earnest intentions. It’s not that voters are wrong — it’s that the poll is. And the publication behind it is infering that it states something it’s simply not capable of determining.

Jeanne Dielman: Signal or Static?

Let me be clear: Jeanne Dielman is a spectacular film and much of the ire directed at it in the aftermath of the list drop was entirely misguided.

It’s daring, formally radical, and one of the most honest portrayals of identity and femininity ever captured on film. As a means to draw attention to a highly deserving picture that few non-cineastes had ever heard of, I somewhat cheer that far more people were sent scrambling to see it, echoing my thoughts on L’Avventura’s surprise debut at #2 on the Top 10 in 1962 (a story coming soon to SINephile).

However, it's so challenging in length and format that it borders on the cusp of experimental cinema. That doesn’t make it unworthy for inclusion, but it was instantly recognizable by almost everyone as an incredibly strange choice for the single Greatest Film of All Time — especially when so few who've seen it, loved it and perhaps even voted for it, would’ve claimed it as their own personal favorite film ever.

So, let's break it down by starting with what the poll DOES say about Jeanne Dielman:

More people believed that Jeanne Dielman belonged *somewhere* on the Top 100 than any other film.

Aware of the prior 2012 poll results, voters thought a female-helmed picture should be higher on the list than at #34.

That's it. Nothing relating to its exact rank.

You may think, "Well, why would I want to know THAT?"

To which my response would be, "Exactly. It's too high-level to be useful."

So how did it rise to the pole position? Because voters, perhaps unconsciously and certainly not in collusion, were trying to correct for past underrepresentation of female directors in the canon. And Jeanne Dielman became the inadvertant strategic beneficiary.

The film was on a lot of voters’ 10-lists not because they thought it was best film ever made, but simply because they wanted to see better billing for the previously highest-ranked woman-directed film on the list. Not complicated and certainly not conspiracy.

It wasn't an endorsement of supremacy. It was a collective signal: "A female auteur should be on my list." The completely illogical polling design then wildly distorted that signal and editors packaged it in a way that either indicates they don't understand how statistics works or they simply didn't care. My bet’s on the latter.

Strategic Voting and the Unintended Canon

Aside from Jeanne Dielman, let's look at some of the other reasonably derived but largely crazytown assumptions from the same poll and we see similar troublesome patterns emerge more broadly, all the result of lousy survey methodology.

POPULAR CLAIM:

"Jordan Peele's fantastic 2017 film Get Out tied with five other films for last on the Top 100 in 2022. So, it's now considered better than Lawrence of Arabia, Raging Bull, Godfather Part II, Chinatown, Nashville, or The Seventh Seal, given that all of those films got cut.”

REALITY:

Wrong. The poll doesn’t say that at all.The departure of those films is the unintentional result of “strategic voting" by individuals with an extremely limited number of votes to:

a) Protect films they feel strongly should stay

b) Elevate films they think are deserving of being on the Top 100With each voter only able to pick their Top 10, Lawrence and company were the movies folks cut from their personal lists most frequently to make room for others. The poll can claim no intent on behalf of voters to remove any film from the Top 100 because no one could vote for a Top 100. In many cases, it's logical to believe that some people cut them simply because they assumed they were other voters’ mainstays and didn't need their vote to stay on the list.

POPULAR CLAIM:

"It doesn't make any sense that Jeanne Dielman is #1, and Claire Denis' Beau Travail landed at #7 when so many of the other films in the Top 10 stayed in the same place unless there's some ‘woke mob’ conspiracy to insert them there."

REALITY:

Wrong. This accusation spread like wildfire on social media in the aftermath of the list’s release.Just as with films that got the boot, strategic voting in a repeated poll has another inherent flaw that results in specific entries remaining static, particularly at the top of a list.

Due to the "bandwagon effect" mentioned earlier, many voters will look at the prior 2012 results and go:"Oh, yeah, Citizen Kane, Tokyo Story, Vertigo, 2001, and Man with a Movie Camera should all definitely stay in the Top 10. So, I'll keep those on my list to stick with the majority opinion and use the other half of my ballot to indicate what I want to help get onto the Top 100."

And that's exactly what we saw happen.

Those five anchors in the Top 10 barely budged while pandemonium set in practically everywhere else. Similarly, we saw outsized jumps in ranking among films that nearly everyone predicted would see their standings rise, and the skewed severity of those increases is inherent in the flawed nature of the poll.

For instance, let's again look at female filmmakers. Most were ready to admit it was somewhat embarrassing that the work of only two female directors was represented in the 2012 poll results. Voters were likely to aim for a correction here with their limited individual capacity to contribute.

Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962): She didn’t climb the ladder. She took the elevator 188 stories straight to #14. In addition to Dielman, Beau Travail & The Piano, I predicted online in the lead-up to the S&S poll update that Agnès Varda's Cléo from 5 to 7 would rise from #202 to take a spot in the Top 100. I did *not* expect it to jump 188 spots to #14. Nor, I'm sure, did practically anyone who voted for it.

This wild swing is another flaw introduced by the confluence of poor polling methodology.

The Top 250 results from 2012 were widely available, and people were going to look for the female-directed features most likely to get elevated into the 100 from the runners-up list. That’s how I made my prediction and it wasn’t terribly prescient of me to do so.It's yet another example of the bandwagon effect and strategic voting emerging from a repeated poll, with the noise ampliifed by individual voters’ limited capacity of picking only ten films and cramming their few strategic (i.e. non-true-Top 10) votes into the back half of their ballots.

And guess what? En masse, voters elevated every female-directed feature on the prior Top 250 in almost the exact same order they appeared on the 2012 list (with a few newcomers sprinkled in).2012:

Dielman > Beau Travail > Meshes of the Afternoon > Cléo from 5 to 7 = Daisies = Wanda > The Piano

2022:

Dielman > Beau Travail > Cléo > Meshes > Daisies > Wanda > The PianoMeshes likely took the sole — slight — hit because it's a decidedly experimental, not narrative, short film.

What's surprising about that result? Nothing.If you think it’s coincidence, given they’d doubled the size of the voter pool since the prior poll, you’re fooling yourself. Voters were attempting to correct for prior bias in a repeated poll. On an individual basis, I’d call that admirable. And the terrible survey methodology then skewed their intent into a result that no one intended.

So it wasn’t some mass conspiracy. It was amplified noise erroneously packaged as intent.One film I'm particularly delighted to see benefit from a Sight & Sound reset, regardless of the reasons behind it, was Do the Right Thing.

That film shamefully sat at #127 back in 2012, despite being one of the most transformative pictures of the last half century, well beyond its surface context of race relations in the U.S.

I’d long proclaimed Do the Right Thing belonged in the Top 20 without thinking it had any chance of rising that high. Instead, it jumped 103 spots to land at #24, and polling flaws or not, I’m personally quite pleased with that result as not an overcorrection.

POPULAR CLAIM:

"Sight & Sound has destroyed the list by inviting too many new voices who threw out a lot of unquestionable classics in favor of contemporary cinema."

REALITY:

I can't simply state, "Wrong." That's an entirely subjective viewpoint, but it lacks essential context.

The shift isn't remotely surprising, nor is it all that unwarranted, and no one purposefully "threw out" anything. Nor were they really capable of doing so.I also predicted prior to the poll drop that we'd see some paring among the works of OG masters of cinema that were likely over-indexed if we wanted to have a list more representative of contemporary film.

The order I called the likelihood of cuts was:Bergman > Bresson > Dreyer > Godard > Tarkovsky > Hitchcock

And that was precisely the order of works cut, with the last three spared.

I also wrote about the relative lack of representation for contemporary cinema (post-Golden Age of Hollywood or post-1970), risking the list's relevance to an increasingly apathetic public, the average age of whom saw very few films listed among the 100 Greatest (single digits) made in their lifetimes. So, everyone would be upset about something for this issue to get properly addressed.

They needed to expand the voting pool to address it — which they did. Nowhere are the poll's inherent flaws more evident concerning modernization than David Lynch's Mulholland Dr. landing at #8. To be sure, the film was relatively high already, debuting at #28 in 2012.

However, this is yet another "bandwagon effect" bias of a repeated poll in which many voters simply looked at the existing list, identified that it also needed to be more contemporary, picked the most recent film on the list, and strategically elevated it en masse to their own Top 10s.

Just as with Dielman, the public cannot assume this to mean "voters think Mulholland Dr. is the 8th Greatest Film of All Time," even though the list implies this. Likewise, voters cherry-picked other films from 2012's Top 250 to elevate for modernity’s-sake, with Spirited Away and My Neighbour Totoro leap-frogging others into the Top 100, to represent modern animation.

POPULAR CLAIM:

“Fine, make the Greatest Films of All Time list more contemporary, but why include X film from a few years ago just because it was popular and remains fresh in people's minds?"

REALITY:

As for more recent pictures from the 2010s, I've long maintained that I'm of mixed opinions... While S&S purposefully (and rightfully) leaves the term "greatest" to the subjectivity of those polled, voters have long been shy of over-indexing on recent films, primarily because they're following one of the few pieces of guidance set out for them in the poll criteria:“Films should be considered to stand the test of time.”

They're trying to ensure voters process past “recency bias” and have the needed perspective that only time provides to evaluate an entry against the nearly endless canon of films over the past 130 years.

For an even better illustration of why that's so important than I can muster, watch this marvelous clip in which director Nicolas Winding Refn interviews the late William Friedkin in 2015.When Refn unfacetiously claims that his own 2011 film Drive, made just four years prior, is every bit as good as Citizen Kane and 2001: A Space Odyssey, Friedkin laughs in his face. He also repeatedly asks the camera crew to fetch a medic to haul Refn away before proceeding to school him on the critical difference between confidence and arrogance, explaining that even he's uncomfortable comparing films he made 50 years ago (The Exorcist, French Connection, etc.) with the greats of classic cinema. It's genuinely cathartic to watch.

But this is all human subjectivity, and it's understandable why some may lean into impaired judgment to promote films they genuinely love and believe will ultimately meet the criteria someday. S&S permits this by requiring that films have theatrical releases only before the current polling year to be eligible.

Granted, four films on this list were released just a few years prior to the survey, so the votes for those movies ignored Sight & Sound's limited guidance because by definition, there simply hadn’t been "time" to evaluate their legitimacy as a timeless pillar of cinema.

In my pre-poll prediction, I claimed that if any films from the most recent decade were worthy of inclusion, they were (in order):Parasite > Moonlight > Boyhood > Roma

Parasite (#90) and Moonlight (#60) made the list (in reverse order), and I can't say I'm entirely unhappy about that if we view the poll results as a living document at least partly reflective of its time.

The debate should never have morphed into whether any of these films are worthy of inclusion — only about whether the methodology can support the conclusions being drawn.

So What Can the Poll Tell Us?

Despite all its failings, the BFI’s list is not entirely useless — only that its rankings are largely meaningless now. Here’s the high-level of what we can reasonably still extract:

Every film listed is broadly deemed of importance and worth seeing.

There’s lasting curatorial value in determining what shows up frequently on ballots. Tastes may vary, but typically these films should be seen as essential viewing for admirers of the art form.There is a visible corrective shift toward diversity across a multitude of spectrums.

Compared to the 2012 list, clear trends emerge of the voting pool attempting to compensate for perceived bias in the prior results. A focus on elevating women's voices, those of other marginalized groups, as well as contemporary and 3rd world cinema was enough of a priority that voters used a portion of their limited ballots to help address it. En masse, this caused unintentional deletions and wildly skewed rankings away from being intent-driven.

The fault of the poll, not the voters.Obsessing over exact positions in the S&S ranking is a mistake because the poll's design would need a massive overhaul to measure voter intent correctly and present itself as any sort of ranking with a straight face.

So, if you want to blame something, blame the brokenness of the survey. The voters operated out of a sense of altruism.Remember, all art (including film) is a collective reflection of ourselves. When the work ceases to represent us in our entirety, the promise inherent in that art is undermined.

Some sacred cows are still sacred.

Citizen Kane, Tokyo Story, Vertigo, and 2001 barely moved. Which tells us that while voter behavior may shift, mainstays on the list (particularly post-2002) deserve even more attention than they typically receive.

Many clearly remain top-of-mind with voters using one of their precious ten votes to safeguard as “true Top 10.” Terrible poll design bumped some films that got cut, so readers cannot assume the inverse is also true.Strategic voting is real and it isn’t going anywhere.

Unless the poll design changes, compounding this effect with each of the aforementioned methodology biases will only make the results increasingly less credible as indicative of voter intent over time.

How to Fix It (or at Least Make It Honest)

Kill off Limited Voting.

It doesn’t work in this context. If Sight & Sound intends to publish a Top 100, then collect Top 100 ballots — don’t infer one from a bunch of unranked Top 10 lists. Not with all the other polling design flaws already compounding the distortion. Even if you still plan to publish the 150 runners-up, extrapolating results out 2.5x from your data set is a whole lot better than 10x.I get it: after the expansion to 100 in 2002, limiting ballots to ten films was a way to reduce “response burden” and encourage participation. But Sight & Sound has since increased its voter pool elevenfold. They can afford some attrition from an otherwise hyper-engaged base.

Transition to Ranked Ballots using weighted composite scoring.

If they insist on keeping limited voting to individual Top 10s, don’t couple it with the poll’s original equal-weight, open ballot system.

Ranked Ballots would have a slight dampening effect on strategic voting and better capture intent behind the ranking of films the higher they sit on the list. Correcting prior voter bias, like occurred broadly in 2022, would still be possible, just not to the wildly unintentional extent that we saw this last go-around.Cease publishing the 150 runners-up list.

As interesting as the info may be, they should immediately stop revealing those films that didn’t quite make the cut (particularly harmful that’s it’s also ranked), which we've seen clearly injects massive bias into the poll results.

Stop handing voters the cheat sheet.

S&S is not going to solve the problems inherent with repeated polls because that's the very nature of this survey at its core. So, they have to compensate elsewhere and this coda is the biggest handicap.Randomize your data set.

Broaden the voter base without depending on strictly in-house editorial nomination and stochastically include qualified participants in the final survey or select data from a randomized sample of the broader eligible base. Also, given the wider participant pool, proactively monitor and correct for non-response bias among legacy participants who may drop out after having seen the 2022 results.

Interestingly, Sight & Sound has since rearranged how it presents the results on its website.

Rather than listing the Top 100 led by a traditional #1 and separating out the 150 runners-up, the poll now defaults to a reverse-order countdown of all 250. It’s a quiet reflexive reframe that sort of adds insult to injury — like trying to “neutralize” the problem by burying it in a longer scroll. But the change speaks volumes.

In another likely response to criticism, the BFI also since published every individual voter ballot from the 2022 poll — something they hadn’t done with this level of specificity before. Whether intended as an act of transparency or deflection (perhaps, both), it shifts some of the focus away from the aggregated outcome and toward the fragmented voter intent behind it. The result is a fascinating data set… and an even messier canon.

Bonus takeaway: check out the Director’s Poll for comparison. It suffers many of the same structural defects, and several similar trends are visible, but the impact is far less chaotic. Why? The voter pool is smaller and more focused — about one-third the size of the main poll — and the responses read as more ideologically consistent and intent-driven as a result.

Final Reel

Let’s be honest: Jeanne Dielman going viral was probably the greatest thing to happen to Sight & Sound thus far this century. They got a visibility boost. They dominated the discourse for a few weeks. They made #FilmTwitter implode. In an attention economy, maybe that was the goal all along. Perhaps the noise really is the point now.

But if Sight & Sound wants to retain its relevance beyond the decade-to-decade media cycle, it needs to shore up the integrity of its process. I still decided to watch the 16 new films I hadn't yet seen from the 2022 list. Because flawed methodology aside, the recommendations are all still noteworthy.

But the rankings? They’re garbage. Not just for Dielman, but throughout most of the stack. They’re a reflection of a deeply flawed survey design and good intentions gone statistically sideways.

Again, don’t blame the voters. Blame the format.

And if Jeanne Dielman got you to peel back the layers (and maybe a few potatoes along the way), like it did for me, maybe it really is doing something truly great after all.

See you in 2032. Bring snacks.